Strategies for Finding Your Kentucky Ancestors

You know that feeling – that little thrill – you get when you find a clue that helps you piece together the puzzle that is your family tree? Well, it recently happened to me. I had been working on an ancestor, my 4X great-grandmother Barbary McKinsey (b. Scotland,1791-).

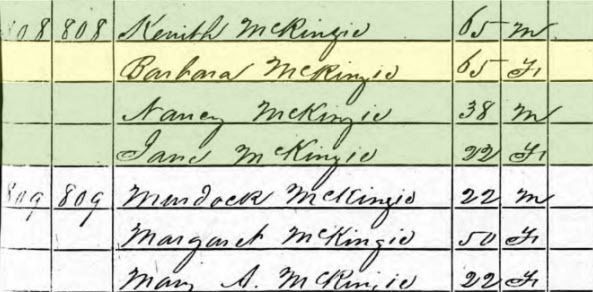

On the 1860 US Census for Hopkins County, Kentucky, I found a new person living with the family: Magret McKinsey. I didn’t recognize her, so I double checked the 1850 US Census to see if she was listed. Well, she was and she wasn’t. She wasn’t living with the family, but she was living next door to the family.

1850 US Census Hopkins County, Kentucky [Source: Author’s collection]

This new information gave me the clue I needed to figure out who Magret (Margaret) was. Now I more carefully peruse not just the family information for the person I’m seeking, but everyone on the same census page, the previous page, and the following page. Using this strategy of checking out the neighbors, I’m finding useful puzzle pieces.

Indeed, noted genealogist John Frederick Dorman (who, sadly, passed away in 2021) often gave similar advice. He encouraged genealogists to expand their strategies in order to find those clues to our family tree puzzles.

Here are some notes from a presentation he gave to the society around 1977 about researching in Virginia.

Strategy 1: Friends, Neighbors, and Kin Lead the Way

First families led the way for relatives and friends to follow. If you don’t know the origin of your particular ancestor, finding the origin of one of these family members or friends may lead you to the origin of the person whom you are researching.

What records should be searched to get clues to a place of origin? The answer, of course, is everything that can be found. Certainly, we should determine just when the ancestor arrived in the county where the family was known to have lived.

Who were the neighbors; who witnessed the deeds and other legal documents? Were there other families of the same surname in the vicinity and were there indications they might have been relatives? If so, will any records of these other families suggest where they lived previously?

Strategy 2: Court Records Have Many Clues

Don’t limit your court record searches to just marriage, deeds, and wills. Proceedings of the county court, including the minutes of sessions, can provide many clues. They are often not indexed, so are tedious to sift through, but you may find the rewards are worth the time spent.

Court proceedings may lead you to lawsuits in which your ancestor was a party. Many of these suits were debt-related, either owed by your ancestor or owed to your ancestor. If your ancestor was sued for debt soon after arrival in the county, the debt might have occurred in their previous place of residence, and the paperwork will show where this was.

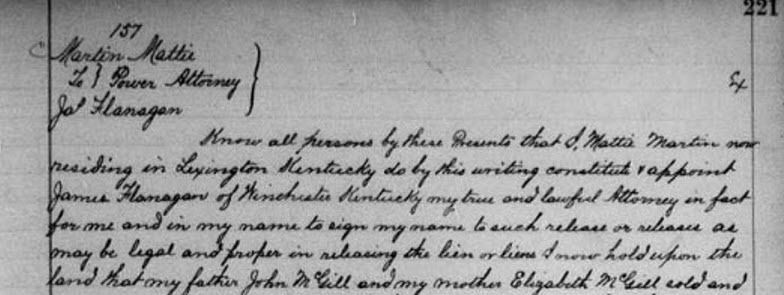

1889 Clark County Kentucky Court Books. Power of Attorney for Mattie Martin that established her residence and her parents. [Source: Family Search Court Documents ]

In southern states, suits over the title to an enslaved person would often contain depositions that tell how the enslaved person was acquired and would specify, if by inheritance, the name and location of the earlier owner.

Court records may show that your ancestor gave a power of attorney to a lawyer for business purposes. A power of attorney had to be acknowledged in court and then entered in the county records. If a power of attorney was acknowledged but not entered in the county’s records, then it probably was intended for business use in a different county or state.

Finding out where the lawyer who held a power of attorney lived or conducted his business will give you information about the location of your ancestor’s business dealings or prior residences.

If a power of attorney was given to a lawyer who lived in the same county as your ancestor but it was not entered in the court records, try to find the lawyer’s county of origin. They may be traveling to conduct business for your ancestor in that original county. The date of arrival in a locality is of particular importance since it will pinpoint the time to be searched in other localities. Although remember that records created long afterward could contain the identifying clue and don’t limit your investigation to too narrow a timespan.

Strategy 3: Consider Details in Other Records

If your ancestor purchased their first tract of land after their arrival in a county, the deed would probably describe them as a resident of that county. But if your ancestor first made a trip of inspection, found good land, made a purchase and then returned home to bring the rest of the family to the new territory, the first deed may have mentioned their place of previous residence.

Biographical sketches published in county histories, especially those issued in the 1870s, 1880s and 1890s, contain much valuable information. Are neighbors and friends who can be identified in the records of the county where your ancestor lived the subjects of biographical sketches in a county history? Such sketches would most likely identify the counties from which these families came.

An investigation of the records of these counties may reveal something about your ancestor, or at least suggest that there were families of the same surname resident there – families who should be investigated further for possible connections.

Assembling the Puzzle

So, to find as many puzzle pieces as possible, incorporate these strategies into your ancestry searches:

- Thoroughly read the census documents

- Search for places of origin for family, friends, and neighbors

- Search county court records and proceedings

- Look for local county family histories and biographical sketches that may contribute to your knowledge of your ancestors.

As always, use your critical reading and thinking skills to evaluate these clues; if the information doesn’t fit fairly closely, then it isn’t the piece to your puzzle.

Resources

The following sources are useful:

- Kentucky Court Records

- Family History and Genealogy: Local Court Records

- Kentucky Court Records: A Guide to Courthouse Research

- General Genealogy Research in Kentucky, Including Court Records

- Special Collections and Archives: Family Histories

Editor’s Notes

In 1977, our Bluegrass Roots magazine contained an article based on the “Before They Came” comprehensive speech by John F Dorman, a professional genealogist from Virginia. Special thanks to our author for updating the article and ferreting out some useful links.