Doesn’t Everyone Have a Birth Certificate?

It is easy to assume that everyone has a birth certificate in our modern information age, and to further apply this assumption to other vital records such as marriage or death. But vital records are a relatively modern development. The impetus for their creation has roots in property law and the protection of individual rights, but what provided the momentum for their adoption was their value to health professionals as modern medical science took hold.

Records Kept for Property Settlements

Exploring the context for vital record creation is important for understanding their timeline of development and puts into perspective the collection of vital records in Kentucky on the national stage. Reviewing this history highlights the years in which vital records were kept in Kentucky, the extent to which they were recorded and why, while also illustrating other potential sources for records outside of those legislated by the state.

Keeping records of significant life events like birth, marriage, and death was customarily a role played by the church in English history. As early as 1538, this role was a requirement, as weekly registration of christenings, marriages, and burials was expected of all parishes in England.

The Grand Assembly of Virginia brought this expectation to America in 1632 when they “passed a law requiring a minister or warden from every parish to appear annually at court on the 1st of June and present a register of christenings, marriages, and burials for the year.”[1]

At this time, the records served as statements of fact, used in the protection of individual rights, particularly the distribution of property and estate settlements. The importance of these records for legal proceedings shifted the focus of the responsibility for their collection from that of the church to the state, as reflected as early as 1639 in the colony of Massachusetts and shortly thereafter by Connecticut and Plymouth.

Legislation continued to be passed and amended over the next century and a half, calling upon government officials, like town clerks, to administer the acquisition and recording of this information. None of the early registration laws proved to be effective outside of a few larger cities. The protection of property rights, which served as a justification for the collection of this information, failed to motivate a population on the move, harkening the call to the western frontier.

Newspaper Advertisement seeking heirs of estate (Kentucky Gazette)

Analyzing the New Found Data

Far from the frontier, new uses of the records being collected were found in the Old World. Mathematicians in England and on the European continent discovered, through an analysis of the records, that they could discern patterns. Astronomer Edmund Halley showed this through the development of the first life expectancy table in 1693.

Cotton Mather applied one of the earliest statistical uses of the records when noting the impact of a severe smallpox epidemic in Boston upon the public compared to those inoculated in 1721. This example illustrates how registration efforts were being made in parallel to the rise of local health and sanitary revelations. Though initially unconnected, health reformers eventually saw the records’ value for demonstrating the importance of sanitary reform and quarantine measures. The need these healthcare professionals had for more accurate information led many to press for more effective registration laws.

Source: William Loftus Sutton, M.D., 1797-1862: father of Kentucky State Medical Society and of Kentucky’s first vital statistics law

Inspired by the efforts of Lemuel Shattuck of Massachusetts, who had been inspired by those of Edwin Chadwick of England, Kentucky physician Dr. William Loftus Sutton began advocating for state legislation of the registration of births, marriages, and deaths in 1850 in Kentucky.[2]

Through the influence of the Kentucky State Medical Society, which he had founded in 1851, he eventually succeeded with the passing of Kentucky’s first Registration Law that same year. Arguments made by Jas. M. Shepard, as part of a committee formed to explore the possibility of a registration law, featured justifications for vital records collection as illustrated previously.

The quote below should sound familiar with its suggested use of the records for protecting individual rights:

“The equitable descent and distribution of estates often depend almost entirely upon the evidence which the registers would furnish of the personal history of individuals; and it requires but a partial acquaintance with the proceedings of courts of law to show how important such a register may be in settling questions as to marriage relation, title to estates, and the rights of heirs at law. Advertisements hunting up heirs of estates are not uncommon; and some say by an eminent English jurist, ‘that it appears fully as necessary for the preservation of the rights of individuals to keep a register of births, marriages, and deaths…”[3]

Shepard quotes Lemul Shattuck when advocating for the value of the registration of vital records for public health. Kentucky’s first Registration Law shows the culmination of thought regarding record-keeping of this nature, considering those arguments used leading up to the 1850s and joining a national and global movement to ensure the documentation of these life events.

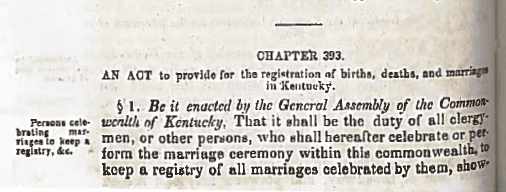

Acts of the General Assembly, 1851-52 Act for the Registration

Prior to the legislation in 1851, there was no state authority involved in the registration of these events. Kentuckians, like those before them, relied upon the church or family to keep track of events like christenings, marriages, and burials. For those looking for records of birth or death, in particular, prior to 1852, these family and institutional records are the sole sources upon which they can rely.

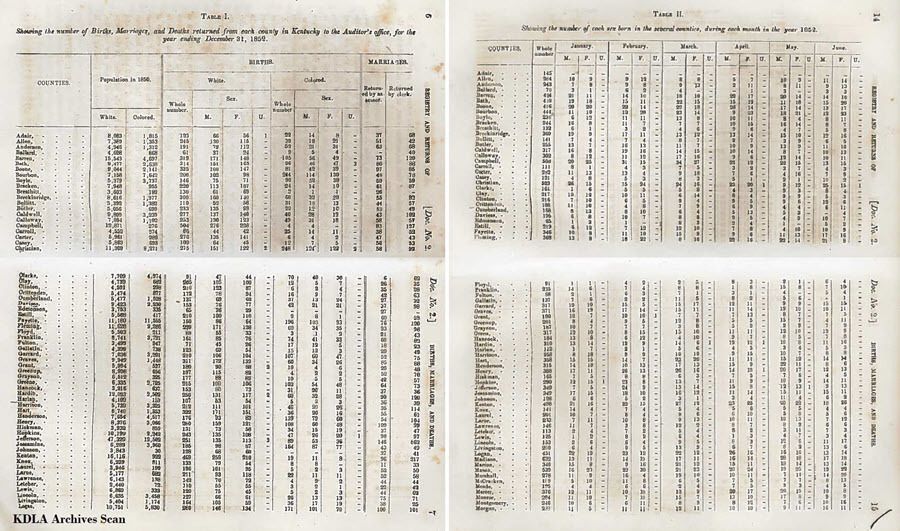

Establishing a Registry of Births and Deaths

Beginning in 1852, the state called upon clergymen, physicians, surgeons, and midwives “to keep a registry of births and deaths at which they have professionally attended” and to deposit their registries with the County Clerk at the beginning of each year. Clerks were instructed to make lists of the births, marriages, and deaths to have occurred in their county, based on these registries and upon inquiries to all heads of families. Upon completion, the clerks submitted the information to the State Auditor. In his first report on the registration law to the State Assembly, the Auditor noted: “that although there are many imperfections and some very gross negligence, yet all together, the enterprise has been eminently successful.”[4]

The Auditor noted the impossibility of completing the duties assigned to his office by the legislature and his procurement of the services of W.L. Sutton for the responsibility instead.

Despite, or perhaps due to, his passion for the project, Sutton could not help but note the challenges of collecting accurate data and the incompleteness of the records being made. He more succinctly summarized “the causes which had made some returns defective” in his second annual report, listing first “the indifference of the people, next the carelessness and neglect of the assessors in collecting the data” and finally, the inadequate compensation given the assessors for the tasks assigned.[5]

Despite its shortfalls, the Registration Law received acclaim and praise from many medical journals. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal wrote that “the report shows a very promising beginning and reflects much credit on Doctor Sutton” while also noting that “some dozen or more states now have registration laws and we are glad to learn… that the subject is actually in successful operation west of the Alleghenies.”[6]

Kentucky Leads the Way in Record Keeping

According to the Nashville Journal of Medicine and Surgery, “the people are slow to believe in using careful registration of such facts.The Commonwealth of Kentucky is the only one West of the Alleghenies, which has yet profited sufficiently by the lessons of the older countries to carry out such a regular registry and its legislators have been wise enough to continue it.”[7] By the fifth year of the report, adjacent states were writing to Kentucky for copies of the law and the registration blanks, and Ohio had adopted a large portion of Kentucky’s law in its own Registration Act.

Recognition of the value of the registration of vital records was not as forthcoming from within the state as out. In the 1855 Kentucky Legislative session, they attempted to repeal the act. Though it failed, it showed the lack of popular support for registration and reflected the poor participation experienced throughout the state.

Dr. Sutton conceded this point in his annual reports, which he continued to complete until 1858. He regularly called out the carelessness of the documentation produced by the clerks and assessors, and each year listed the counties that were completely negligent in reporting anything. The causes of death were suspect having come from men with no medical training, and even such facts as race and sex were sometimes difficult to determine from the information provided.

Kentucky Annual Report from the 1850s

Collecting Data is a Hard Task

In 1859, the Act was amended to appoint the position of a State Registrar. Dr. Samuel M. Bemiss accepted the position and like Dr. Sutton before him, enumerated the difficulties in enacting an efficient registration system. His frustration culminated in the 1861 annual report when he declared that “no apology for a deficiency like that which has occurred” could be made.

This statement came after reliability tests of the assessor’s returns from Louisville showed a failure to include over 1,200 deaths. This was but one example of the negligence of many officers employed in performing this duty. He estimated a loss of one-third of births; and nearly half of the deaths that occurred in the state.

In 1862, the pressures of war and the opportunity to save on the costs of administering the registration law led the Kentucky General Assembly to repeal the act.[8] The Kentucky State Medical Society and Governor John W. Stevenson recommended that the General Assembly reenact the registration law in the late 1860s. Preston H. Leslie, who assumed office in 1871, took up the cause.

Despite this, Kentucky would not officially require registration again until 1874. Like those before him, the state auditor, D. Howard Smith bemoaned the additional duties assigned to his office. Besides the challenges of guaranteeing accuracy highlighted by Dr. Sutton and others engaged with registration before, Mr. Smith drew particular attention to the costs accrued by his office for administering the law and the lack of compensation accounted for by the legislation.

This culminated in his report in 1877 when he asked “that (he) be relieved of this work for the future, or that such an appropriation be made as will enable (him) to have it done without imposing undue labor on (him)self and subordinates.”[9] They granted his request when, in that same year, the General Assembly repealed the act requiring the registration of births, marriages, and deaths. In its place, the State Board of Health was created and among other responsibilities, was given authority over the registration of vital records. The shift in oversight illustrated the growing association of registration with public health as opposed to individual rights.

Some Vital Records Changes Took Years

Reports from 1879 to 1880 include complaints concerning the difficulty of the task and the inherent errors in its execution, issues that had plagued the law since its inception in 1852. Participation in registration appears to have been especially poor for those years of assumed responsibility by the Board, who stated in their first report that only nine counties had provided returns. Despite statutes that continued to confirm the responsibility of the Board for registration into the 1880s, the annual reports and the registration tables ceased being published in 1880. They would not revisit registration in Kentucky until 1910 when the Bureau of Vital Statistics was formed, and the modern collection of vital records began.

We can see the results of the tumultuous history of registration in Kentucky in the records of the Kentucky Department for Library and Archives. Individuals researching genealogy can turn to the KDLA collections for vital records from 1852 to 1862 and 1874-1878 for most counties, and for sporadic years from varying counties in the years between 1879-1910. Even those records represented in these years have shortfalls, as noted by the challenges that plagued their collection.

Often as simple as lists, as opposed to a modern certificate, the records can challenge the researcher with not only their incompleteness but also their inaccuracies, such as the cause of death. The records are a unique challenge and frustration to many who embark upon the search with the assumption about the ever-present existence of certificates for birth or death. But when approached with the right context and understanding, they are a vital source for genealogical researchers.

Editor’s Note

Our KYGS team appreciates the support from the The Kentucky Department of Library and Archives, you can request a record or get help from an archivist using this page.

References

- Appendix II History and Organization of the Vital Statistics System.

- Goldsborough, Carrie Roberta Tarleton., Fisher, Anna Laura Goldsborough. William Loftus Sutton, M.D., 1797-1862: Father of Kentucky State Medical Society and of Kentucky’s First Vital Statistics Law. United States: Thoroughbred Press, 1948.

- 1850-51 Journal of the Senate of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, page 391.

- 1853-54 Legislative Documents, Legislative Document 2, First Annual Report to the General Assembly of Kentucky Relating to the Registry and Returns of Births, Marriages, and Deaths from January 1, 1852-December 31, 1852, page 441.

- Goldsborough, William Loftus Sutton, MD, 1797-1862.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- 1862 Kentucky Acts of the General Assembly, page 263. An act repealing chapter 82 of Revised Statutes, title “Registration of Births, Deaths, and Marriages.”

- 1877 Legislative Documents Vol. 3, Legislative Document No. 12. Auditor’s Third Annual Report relating to the registry and returns of Births, Marriages, and Deaths in the State of Kentucky from January 1, 1876 to December 31, 1876.