Whether it was to escape economic hardship, seek new job opportunities, or simply start anew, Kentuckians have been migrating westward for decades. From the gold rush to modern-day Silicon Valley, Kentuckians have left their mark on the west and continue to do so today. So join us as we delve into the history of this migration after the War of 1812 and learn about our ancestors who helped shape the American west.

Kentuckians Expanding in the West

Upon the conclusion of the War of 1812, a description of the United States in a classroom could have run:

“The United States, class,” this theoretical instructor of geography might have declared, “is as a triangle, with the base along the Atlantic coast defined by the thirteen original colonies, with the two remaining sides swinging into a point at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers in southwestern Kentucky.”

“Note, class,” said the teacher, “the Great Lake Plains to the northwest, much of which is treeless and therefore not suitable for farming, and the same can be said for the Gulf Plains to the southwest, within the Louisiana Purchase and partly under Mexican control.”

But little did our geography professor reckon with the expansionist pressures soon to burst upon the nation. It was precisely in those two plain areas, in the northwest and in the southwest, that the first manifest destiny tendencies exhibited themselves.

In the beginning, resistance by the [Native Americans] of those areas and poor land routes discouraged rapid movement to the frontier, but by 1850, armed opposition had been overcome, while adequate roads had been laid, over which wagons came, to be supplemented in a little while by faster and more efficient locomotives and steamboats. Little settlement could take place in the Northwest until the [Native Americans] were conquered.

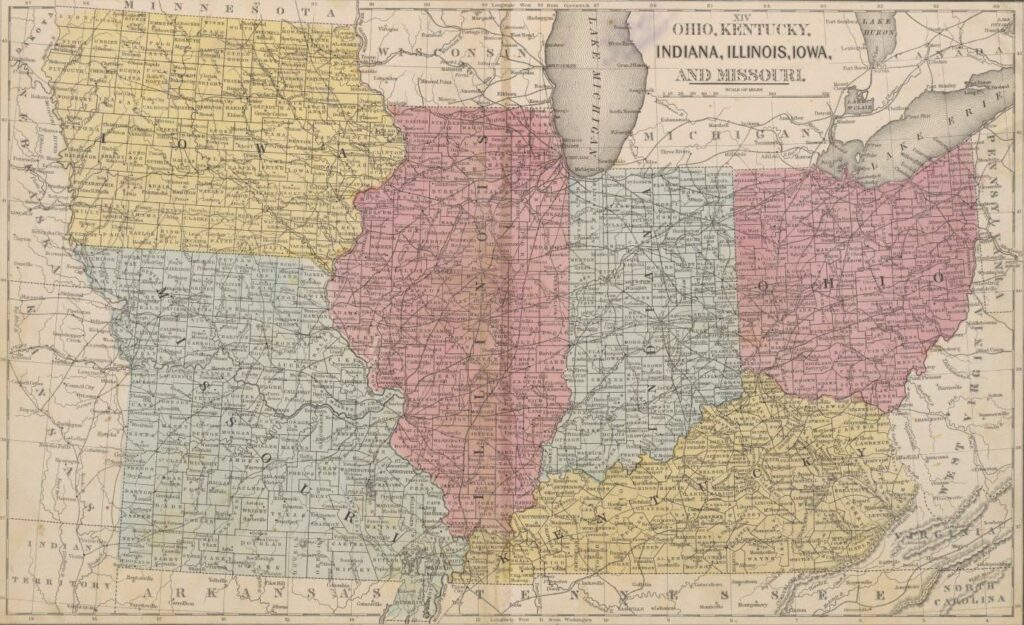

The federal government constructed forts to protect settlers as it cleared areas in Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan. Canadian traders received orders to vacate [Native Americans] villages on American soil. The tribes were notified to either give up claims to the American Northwest or be expelled by military force. The first of the pressures for expansion came early with the crop failures of 1816 and 1817 in Europe.

John Gast, American Progress, 1872. Wikimedia.

Migrating into Indiana and Illinois

The farmers of the Old West moved quickly across the Ohio River into fertile lands in Indiana and Illinois already vacated by the [Native Americans], and began the heavy migration through these areas which continued at a fast pace for several decades. The end of the Second War with England reopened European markets for tobacco and cotton, and it was especially the latter demand that resulted in a strong movement from the Southeast to the Southwest. Older cotton lands had been depleted.

Seeking Better Farming Soil

Wealthy planters sold their worn-out plantations and purchased larger and more fertile acres in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. A few of the poor whites, having no inclination to [enslaved someone], also went West, before the cotton grower’s frontier, and when the plantation owners caught up, the small farmer often sold out and moved further to the West.

One factor, often ignored or misunderstood, was the immediate undesirability of much of this land beyond the geographical triangle earlier described. Southern Indiana and southern Illinois were especially prized, even the hilly sections, because of the general belief that only forested areas contained rich soils. We now know differently, but the pioneer learned slowly to accept the treeless prairie for farming purposes.

The Shelbyville moraine, the limits of the glacial march to the south of the Illinoisan and Wisconsin drifts, marked a dividing line between the rich, loamy soils to the north and the hilly, clay soil to the south. Settlers, later, were to call the northernmost part, “God’s country,” while reserving for the poorer lands the term “Egypt” for southern Illinois.

But in the first few years of migration following the War of 1812, the hilly, forested, clay soils were preferred first, because they were safer and second, because the immigrant found them closer to his previous farming experience.

Map shows counties, existing and proposed railroads, cities, towns, and notable physical features; also areas of Native American habitation for Dakota [Territory], Minnesota, and Nebraska. Relief shown by hachures. [Source: Map Collections from the University of Texas at Arlington and was provided by the University of Texas at Arlington Library to The Portal to Texas History]

Migrating from Louisville

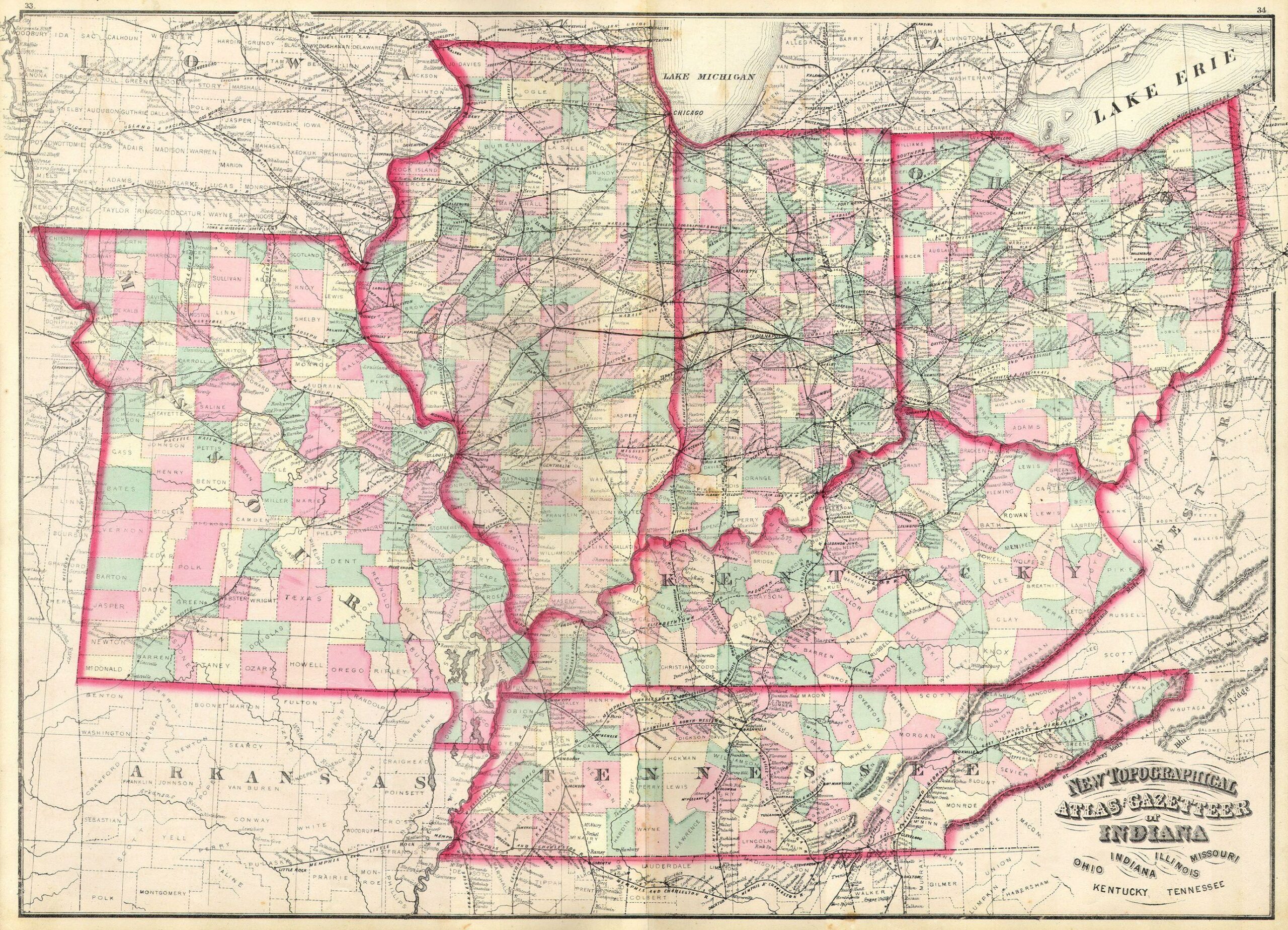

The first settlers of Indiana and Illinois moved westward from Louisville, Kentucky, and from Shawneetown, Illinois, just across the Ohio River from Kentucky.

No other roads existed at the beginning of this migration movement. In fact, it was not until they extended the National Road to the West that the Yankee could move himself and his family to the Northwest without going through Kentucky.

From Louisville, two distinct territorial roads emerged, one to the north and slightly westward in direction to Lafayette, Indiana, and the other, more west than north, to Vincennes, Indiana, and on to other Illinois French settlements and to St. Louis, a new jumping-off place, awaiting only treaty arrangements with [Native Americans] just to the west.

The Shawneetown, Illinois, entry began in Lexington, Kentucky, and its feeder routes, chief of which was the Maysville Road, back of which lay the National Highway from Maryland. From Shawneetown, three different roads advanced the westward-bound immigrants into Illinois: one, north to Albion, another, northwest to Alton (north of St. Louis), and a third, west to Kaskaskia.

Descriptions of travel into Indiana and Illinois from Kentucky depict primitive traveling conditions. Even in the best of weather, the bumpy roads made riding in wagons and carts unpleasant. After a long day of being tossed up and down and back and forth, travelers retired for the evening, fatigued and suffering from sore muscles. Often, the men and boys escaped the rough ride, but were equally tired and probably as sore from driving hogs and cattle ahead of the wagons.

New Topographical Atlas and Gazetteer of Indiana, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee. [Source: Public Domain Wikimedia]

Migration by River

Meanwhile, flatboats and later, steamboats, dropped hundreds and sometimes thousands of immigrants and their worldly possessions further and further downstream to roads leading into rapidly settling areas. Within a short period, the lands just beyond Kentucky were full, and the government soon found itself under pressure to negotiate with the [Native Americans] for additional lands in the Northwest.

Daniel Boone and other early Kentucky settlers were among the first to migrate to Spanish Missouri. The conclusion of the Louisiana Purchase made Missouri territory a part of the United States. What was to become the state of Missouri was also soon to be rapidly settled at the conclusion of the War of 1812.

The [Native Americans] were forced to submit, and after 1815, farmers poured into Missouri through the gateway of St. Louis, some of whom were from Kentucky either directly or through the Old Northwest region. The rivers were the early highways to market at New Orleans. A few Kentuckians went there, examples being Squire Boone and Abraham Lincoln, either to settle or to trade, but Louisiana came to be largely settled directly from the Gulf and from the East rather than from the northeast through the Mississippi River and the Natchez Trace.

Putting Roots in Texas

The first settlers to go to Texas landed on the east coast by water. Moses Austin entered Texas from New Orleans. They established soon thereafter towns and forts on the emigrant roads, which roughly paralleled the coast. The first was the Austin Road beginning at Natchitoches and ultimately ending at Fort Duncan on the Rio Grande. A branch of this road began at a point 150 miles into Texas and ended on the same river about 100 miles west of Brownsville.

Another road began at Fort Gibson on the Arkansas River and marked the western limits of the most desirable land. Kentuckians were in Texas very early. In 1830, a census showed immigrants were coming in from the cotton kingdom, but that most of the 20,000 population were from Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

By 1850, the population had risen to 212,000, with the proportion of the three just-mentioned states continuing high. East Texas, which began with the Austin Colony, was the first to be occupied. North and West came later.

Peters Settlement

The Peters Settlement is of particular interest as its founder, W. S. Peters, and several other leaders immigrated from Louisville, Kentucky. The Peters Colony was the most important and the largest of the grants given by the Republic of Texas. In 1841, the area of the grant given and in following years eventually covered all or part of twenty-six present North Texas counties. Prior to that, Texas was a state of Mexico which prior to the Revolution of 1821 belonged to Spain.

The Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819 established the Sabine River as the dividing line between the United States and Texas. It was in this Spanish period of ownership that Moses Austin got permission to colonize Texas. The work of Moses was continued by his son, Stephen, who established a flourishing settlement at San Felipe de Austin. In 1824, a general colonization law opened Texas further to settlement.

Texas relations with Mexico deteriorated, and in 1836, a revolution broke out. The United States recognized Texas as a state in 1837, and in 1845, Texas joined the United States. Such is a quick sketch of the principal migration routes westward from Kentucky.

Westward Migration Slows by 1890

By 1890, movement had slowed perceptively. The preceding forty years marked a continuing movement to the frontier, as in the gold rush of California, which claimed many curious and energetic Kentuckians. But in the main, the far westward movement after 1850 continued at a distance from the cultivated fields and prosperous farmhouses of those who accepted more permanent residence in Kentucky, and the state played a much lesser role in this later frontier advance.

Editor’s Note

Charles F. Hinds (1923-2019) was a Kentucky state librarian from 1969 to 1979 when he gave this talk to the society in 1974. Mr. Hinds was Director of the Kentucky Historical Society from 1960 to 1963, and then served as the first Director of the Kentucky Archives and Records Service from 1963 to 1967. He passed away 14 Aug 2019 in Florence, Kentucky.