A Marriage Recognized by the Commonwealth was Desired

Thornton and Henrietta Fowler were freed from the bonds of slavery by the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America in 1865. Although President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, the directive applied to enslaved people in states that had seceded from the Union. Thus, enslaved Kentuckians were not directly affected.

On February 9, 1867, the Fowlers visited the Georgetown, Kentucky, courthouse to present themselves to the Clerk of Scott County, J. Henry Wolfe. They declared they had lived as husband and wife for thirteen years and wished to continue living together as a legally married couple. They were the first of many to do so.

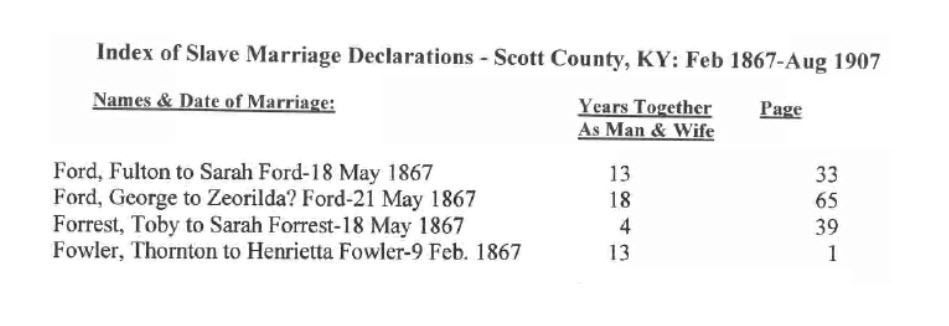

Fowler Marriage from the Scott County Transcription Source: Bluegrass Roots, 2006

Lucy and Parker Bradford came to the courthouse on February 11, 1867, stating they had lived together as man and wife for forty years. Manlius and Queen Thomas appeared four days later to say their marriage had lasted thirty years, and they wished it to continue.

Kentucky Enacts Marriage Laws after the Civil War

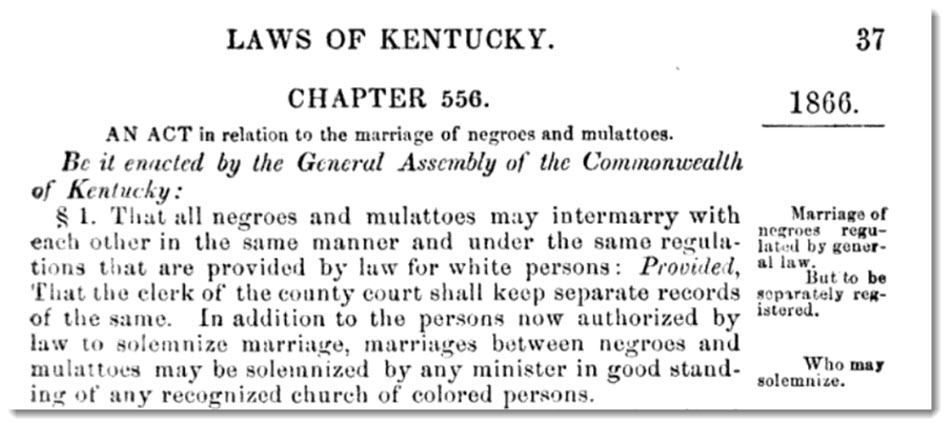

These requests were the result of a law passed by the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky in 1866. This three-part law defined how African Americans could marry, recognized marriages of formerly enslaved persons, and prohibited interracial marriage.

The first section stipulated that African Americans may marry under the same general law as white people, but the records must be kept separately. Any minister in good standing of any recognized church for African Americans could perform the marriage.

The second part stated that all the formerly enslaved persons who have lived and cohabited together and now live together as husband and wife could be considered legally married and their issue held as legitimate for all purposes. Such persons were required to appear before the clerk of the county court of their residence and declare that they have been and wish to continue living together as husband and wife.

The couple was required to pay a fee of 50 cents to the clerk to record the declaration. For another 25 cents, the court would issue a marriage certificate, which was evidence of their declaration of marriage and the legitimacy of the children born to the couple.

The final part specified it should be unlawful for any African American to marry any white person. If this should occur, the persons of both races would be deemed guilty of a felony and, on conviction, subject to confinement in the State Penitentiary, at the discretion of the jury, of not less than five years. The law further defined who was considered a non-white person.

This law was approved February 14, 1866.

Laws of Kentucky, 1866 Source: Google Books

Legitimizing Marriages in Scott County

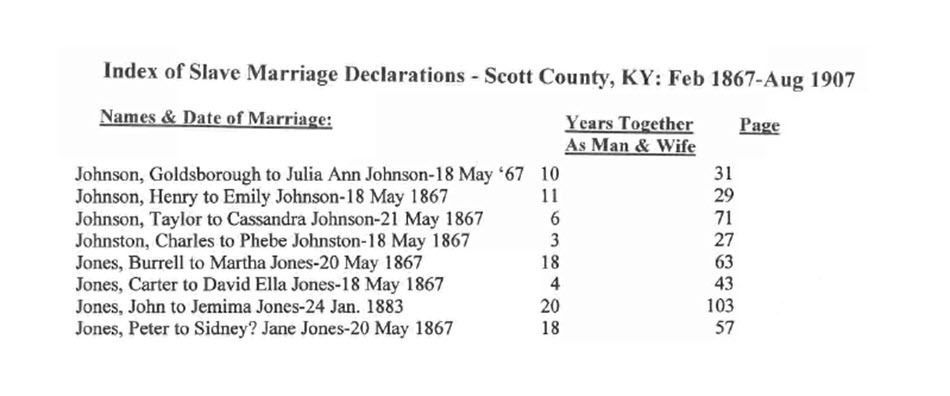

Many formerly enslaved couples took advantage of this legislation to legitimize their marriage and their children. In February 1867, the Scott County Clerk recorded nineteen marriages with twelve more added in March and six more in April. Apparently, the word spread throughout the African American community, as there were 117 declarations of marriages by those previously enslaved persons in May 1867. Couples continued to come forward to declare their marriages throughout 1867. By December, 163 couples had recognized marriages.

Over the next ten years, these numbers would dwindle. From 1868 to 1893, there were fifty-five declarations. The last declaration was made by Peter and Martha Gaines August 24, 1907, the couple having lived together for 47 years. There were 219 recorded marriages.

Choosing a Surname

Prior to 1866, those couples making declarations had lived together as husband and wife. There is a separate marriage register for free persons of color in Scott County, beginning in 1863. Note that prior to emancipation, the enslaved individuals were usually referred to in public records by their first names and the names of their owners. Occasionally, a surname is recorded for an enslaved person, but rarely.

When they became free persons in 1865, the enslaved persons selected a surname, if they did not have one. This explains why in 1867, all but one bride was listed with the same surname as her husband. These brides had none of their own and they went along with a husband’s choice of name. This fact can be very misleading for family historians, as the bride should have been recorded as having no known name.

Brides used husband’s name. The maiden name was not captured (if there was one). [Source: Bluegrass Roots]

It was not until 1875 that one again finds a bride on the list with her own maiden name recorded, rather than that of her husband’s. By 1882, five of the six declarations given that year included a maiden name for the bride. It would appear that these women were achieving their own identity.

The author provided this list of Scott County, Kentucky marriages in the Bluegrass Roots, Summer Edition 2006 available from Member Portal.

References

- 1866 Acts of the General Assembly, University of Kentucky, UKnowledge Digital Archives

- Commentary on Slave Marriages, Bluegrass Roots, Summer 2006

Editor’s Notes

We updated the language in the original post to reflect modern language trends. Any other text was copied directly from the source and thus has the language in use at the time.