They Came to Kentucky for Land to Sustain Themselves

Literally locating your Kentucky ancestors might involve understanding the different ways they attained land. For many, they used the Land Patent Process that is described in this post by expert Kandie Adkinson.

In 1763, King George III of England declared veterans of the French and Indian War would be paid with land rather than money. Bounty Land Warrants allowed surveys of unappropriated land; the amount of acreage depended on the soldier’s rank and time of service.

The Virginia Land Law of 1779 adapted the same method of paying veterans of the Revolutionary War. The Land Law created a military district south of Green River in western Kentucky for Virginia veterans. Land claims of early Kentuckians were also addressed with the development of Certificates of Settlement and Preemption Warrants.

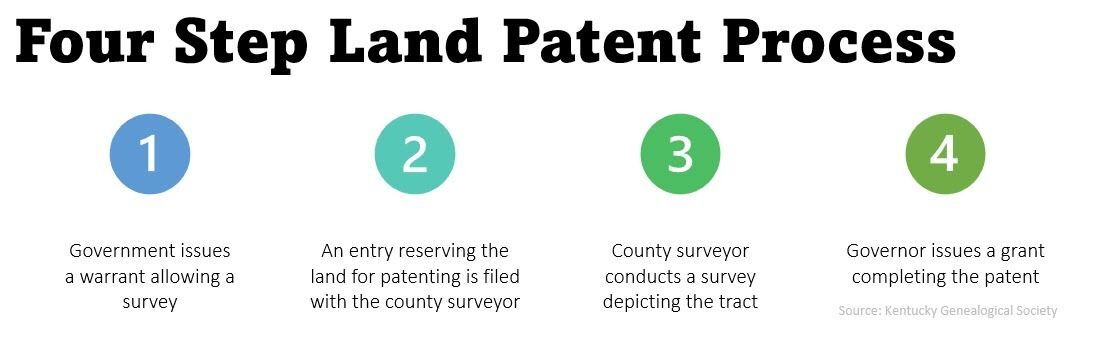

Land Patents were a Four-Step Process

Land patenting was a four-step process. All four steps had to be followed. A warrant was not a title document nor was a survey.

Four Step Land Patent Process [Source: Kentucky Genealogical Society]

Understanding the Patent Process

Simply because an ancestor received a military warrant for service in the Revolutionary War does not mean he took title to the land. Warrants and surveys were assignable—meaning they could be sold in whole or part. Veterans who preferred cash to moving to a military district could sell their warrant, keep the money, and stay home.

There were several speculators or other veterans willing to pay top dollar for the military allotments. They could then combine several warrants to patent large tracts—instead of one veteran owning 100 acres; one speculator could use ten warrants and patent 1,000 acres. It is estimated nearly 80% of all veterans sold their warrants.

Only a small percentage of Kentucky land patents were issued for military service.

Land Grant Series

When researching the land patents, they are contained in nine series:

- Virginia Land Grants (1782-1792)

- Old Kentucky Grants (1793-1856)

- Grants South of the Green River (1797-1866)

- Tellico Grants (1803-1853)

- Kentucky Land Warrant (1816-1873)

- Grants West of Tennessee River Military (1822-1858)

- Grants West of Tennessee River Non-Military (1825-1923)

- Warrants for Headrights (1827-1849)

- County Court Orders (1836-present)

Refer to The Kentucky Land Grants book by Willard Rouse Jillson (free resource) for specific details about each series. The huge volume lists names of those who received a grant. This book is available on Google Docs for free.

There were other ways to gain land. Other land patents were allowed by: Treasury Warrants, Certificates of Settlement, Preemption Warrants, Importation Warrants, warrants for finding salt or clearing roads, South of Green River Certificates, land warrants purchased from the Kentucky Land Office, land warrants purchased from the county court, and special Acts of the General Assembly, such as for poor widows and the relief of certain poor persons.

All records pertaining to each series are filed with the Secretary of State’s Land Office in Frankfort, Kentucky. You do not have to travel to Richmond, Virginia, to see warrants, surveys and grants prior to 1792 (when Kentucky separated from Virginia).

Tips for Understanding Land Patents

Key points to remember regarding Kentucky land patents:

- There were four steps in patenting land: Warrant, Entry, Survey and Grant.

- Kentucky honored military warrants for service in the French & Indian War and the Revolutionary War. Bounty warrants for later conflicts, such as the War of 1812, could not be used in Kentucky. Public domain states, such as Missouri or Illinois, accepted the federal bounty land warrants. This partially explained movement from Kentucky into the western states.

- Revolutionary War Warrants had to be used within the Kentucky Military District in southwestern Kentucky.

- Note: After 1792, when Kentucky separated from Virginia, the warrants had to be used in the Ohio Military District reserved for Virginia veterans.

- No patent required an application form. It would be nice to see a document that listed home state, birth date, and parents’ names, but such a form was not required.

- Deeds were not collaterally filed with the Kentucky Land Office. They were registered on the local level with the county clerk. In the event of a courthouse disaster, the records were lost (if they had not been previously microfilmed).

- Remember county formation dates when researching Kentucky. Your ancestor’s land may have moved to another county when the boundary changed.

- Study county tax lists to determine the name of the person who filed the original entry on a piece of property; the name of the person who had the survey made, and the name of the person who received the patent/grant. Your ancestor may have patented the property or he may have purchased a patent from another person.

- Study all original documents involved in the patent to understand the process fully.

Example of a completed 100-acre land grant for Samuel Mann. The property was near the Licking River and surveyed on 1 Jan, 1823, in Floyd County. After receiving the grant, he gave land to his in-laws, the Dykes, and son. Source: The Kentucky Land Grant book and the FamilySearch Land Records for Floyd County, Kentucky.

Finding Land Patent Documents

There are multiple ways to locate land warrants and grants.

- Kentucky Secretary of State Website offers searchable databases along with many scanned records. It is an excellent source.

- Original warrants, surveys and grants are available on microfilm at the Kentucky Historical Society Library and the Kentucky Department for Libraries & Archives, both in Frankfort. Be sure to copy the front and the back of each record; the back of the warrant or survey could include assignments and signatures.

Editor’s Notes

This post was taken from a Bluegrass Roots post by the author in the Winter of 1999. We made minor editorial changes and added updated links. Kandie Adkinson, the author, spoke to our society in 2018 about land patents.