Early settlers who were determined to find land and opportunities pushed westward in two major ways: by water routes and by land routes. Initially, waterways seemed to be easier than land routes, but they presented their own difficulties.

Uncharted waters, attacks, drownings, and other misfortunes made a water passage a risky undertaking. But, as water travelers became more numerous, they better understood how to build a flatboat or craft and their knowledge gradually increased about the waterways, they learned to prepare for some of the dangers they met.

The second westward push was over the Appalachian Mountains. Passage was slowed when families and livestock joined the Kentucky pioneers. Trails became roads, and the flow of settlers increased to a tiny stream to a flow as people realized the possibilities of a new life west of the Appalachians.

Waterways Were Challenging Routes to Kentucky Settlements

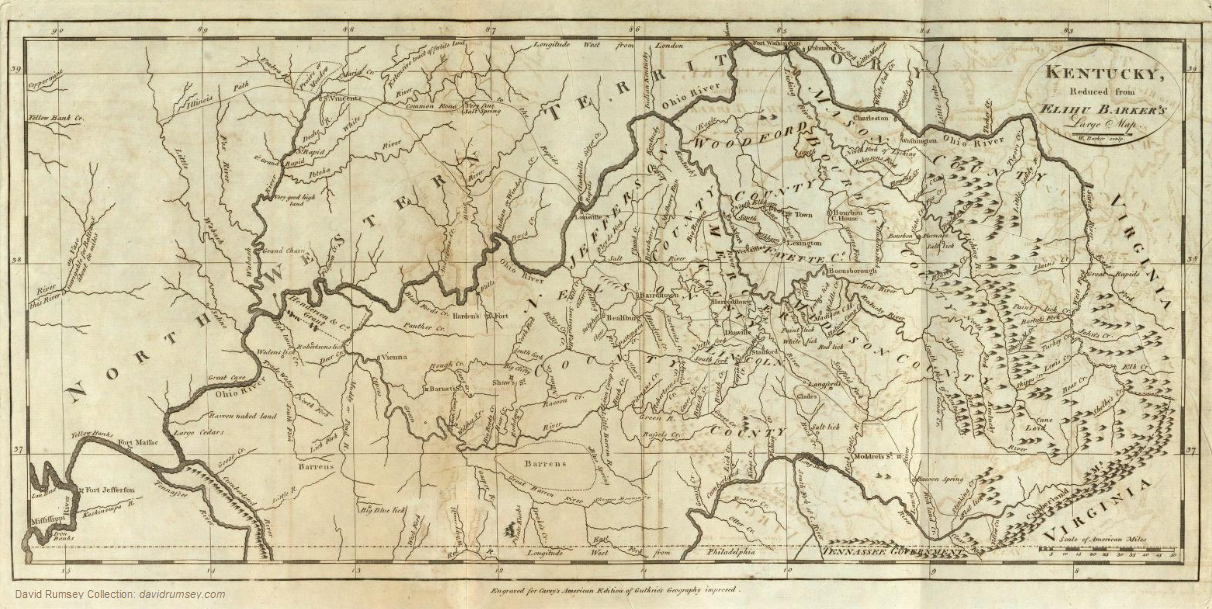

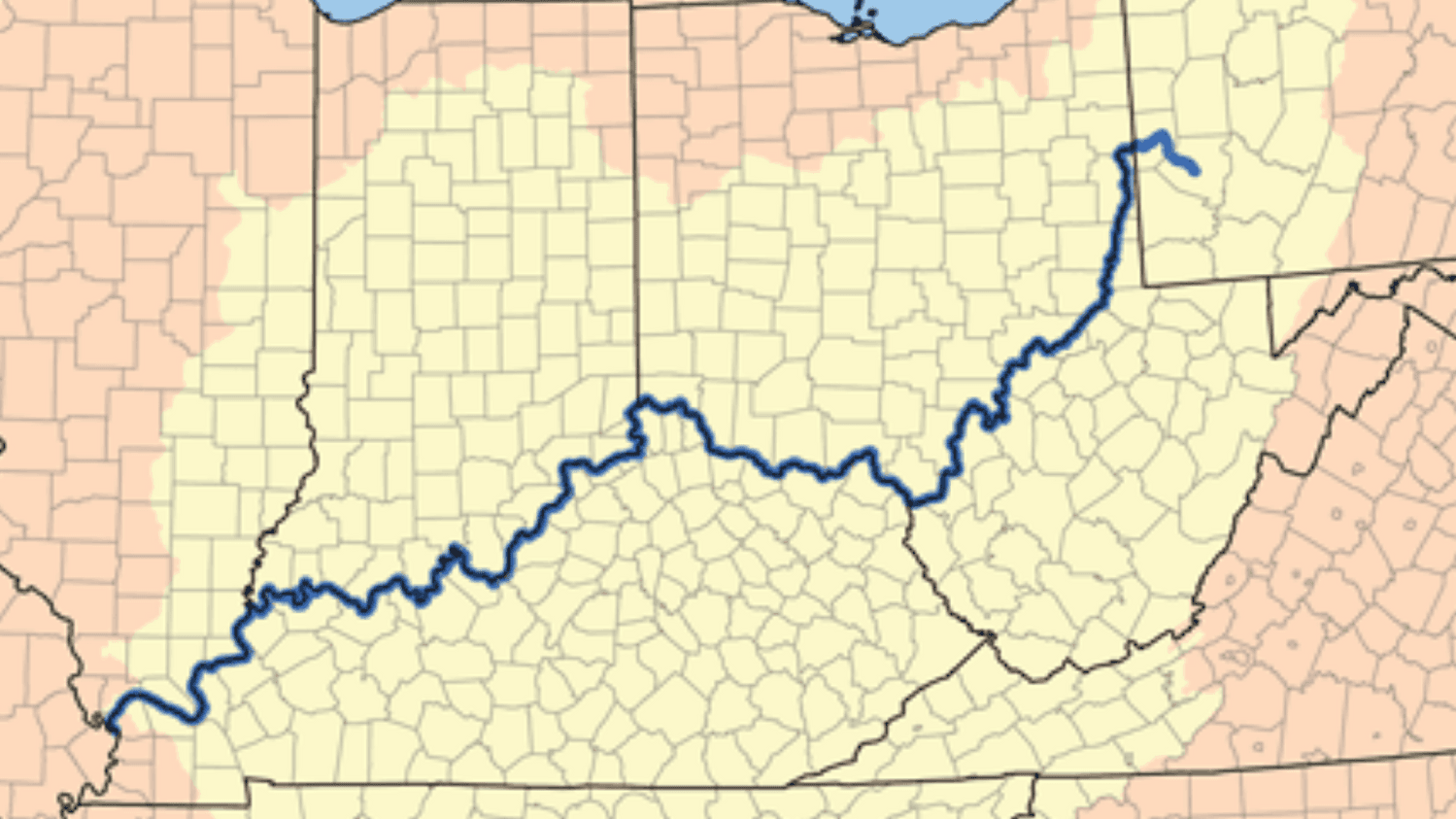

Those early emigrants could, of course, travel to Kentucky by the river route after reaching Pittsburgh (Fort Duquesne or Fort Pitt) on the Ohio. But, traveling the river in the earliest times required braving the wrath of Indians and the treachery of uncharted waters.

In spite of these, many chose the water route. Maysville (formerly Limestone), Kentucky, was a major entry point. Some went down the river to the Falls of the Ohio (now Louisville, Kentucky) before debarking. Others, after portage around the Falls, floated on to Shawneetown, Illinois, before landing and continuing into Kentucky.

Following the waterways into Kentucky Source: Wikimedia

The National Road and Other Access Roads

As land sales were opened in the Old Northwest, funds were appropriated for the building of a National Road. The National Road, in part, followed the Old Nemacolin Path that had been improved as a military road for the troops of General Braddock during his ill-fated march on Fort Duquesne. The National Road originated at Cumberland, Maryland, and crossed the southwestern part of Pennsylvania to the present town of Wheeling, West Virginia. This roadway was extended at a later time (1837) to Zanesville, Ohio, and then on to Vandalia, Illinois. From Zanesville, a trace turned southward by way of Chillicothe to the Ohio River opposite Maysville, Kentucky.

North of Braddock’s Military road was another military road built by the troops of John Forbes during their successful attack on Fort Duquesne in 1758. The road originated at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, turned south to Shippensburg and Chambersburg before turning west to Fort Loudon, north to Ft. Littleton, and finally east to Ft. Ligonier, ending at Fort Duquesne. This road connected with a road from Philadelphia and provided the immigrants with a direct route to western Pennsylvania.

Farther south, the Old Trader’s Path from Augusta, Georgia, to Columbus connected with the Federal Road which was an extension of the Upper Road from Fredericksburg, Virginia, to Salisbury, North Carolina. From the junction of these two roads at Columbus, Georgia, the Federal Road took a westerly direction to Montgomery, Alabama then southwest to the Tombigbee River and west again to Natchez, Mississippi.

The Great Road: Over the Mountains into Kentucky

The most important of the early emigrant trails to Kentucky was the Great Road and its extension the Wilderness Road. It was down the Great Road that the Scotch-Irish and German immigrants flowed from western Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia. Seeking new lands in the Shenandoah Valley, these settlers pushed on until they breached the mountains and filled the beautiful land called Kentucky.

The Great Road rose on the Potomac River at Waskin’s Ferry, went southwest down the Shenandoah Valley between the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains to Winchester, Virginia, through Strasburg, Staunton, Lexington and over Natural Bridge and across the headwaters of the James River to Salem, through Wytheville, Abingdon and to Bristol on the Virginia-Tennessee Border. From Bristol the road continued west and down the Holston Valley to Kingsport, Tennessee.

Daniel Boone Opens and the Wilderness Road

In 1775, Daniel Boone was hired by the Transylvania Company to cut a continuation of the Great Road on to Kentucky. Boone and his crew began at Kingsport and went northwest to Clinch Mountain near the site of Gate City, Virginia, across the Clinch and Powell Rivers to the site of Jonesville, then down the Powell Valley to Cumberland Gap, then north to Barbourville, London and on to Boonesborough where Boone erected a fort. Later a branch of the Wilderness Road from Hazel Patch to Stanford, Harrodsburg, and on to Louisville became a well used migration path.

After 1785 an easier route to Cumberland Gap was opened. This segment of the Trail began at Kingsport, Tennessee, and continued through the Holston Valley to Bean’s Station, where it turned north to Cumberland Gap.

For many years the route into Middle Tennessee was through the Wilderness Road and down the Cumberland Trace to the settlement on the Cumberland at French Lick. In 1788, however, a road was cut directly east from the settlement at Knoxville to the settlement on the Cumberland River.

This great road was the main entry into Kentucky from 1775 to 1800 when the population grew from a few hardy pioneers to 220,955. By their presence, those early settlers saved the west for the United States. They were sturdy people, willing to endure hardship, hunger, and death to establish themselves in Kentucky.

Descendents of those early pioneers have reason to be proud of their heritage.

Editor’s Note

This post is based on the notes from a lecture Edna Milliken presented to the Kentucky Genealogical Society in 1974 Seminar. Edna Milliken (1921-2005) made history as the first female president of the Kentucky Historical Society in November 1963. She had an enthusiasm for history after learning one of her great-grandfathers, Robert Moore, founded Bowling Green. She worked at the Kentucky State Library and Archives. She traveled throughout Kentucky giving lectures about the migration path of settlers through Cumberland Gap.