Where Did They Go?

Every family researcher has had instances of persons who simply disappear from the records without a trace. The individual may be on some reliable record: baptism, marriage, deeds, tax lists, and so on. Then, with no explanation, that individual can not be found on any later records.

Some of these cases have logical explanations: died without a will or property settlement (and before death records were required, or no death certificate was filed); moved to another county or state unknown; or, in case of a woman, married to a man whose name is not known. Occasionally, the woman married a man with the same surname as hers. Researchers might find these situations confusing.

Did Your Kentucky Ancestor Experience a Name Revolution?

In early days, the evolution of a surname was common. Guyot in Normandy became Wiat in Yorkshire, Wyat in Kent and Wyatt in Virginia – all the same family. Or a surname had radically different spellings that defy Soundex, such as Quisenberry and Cushenberry.

Sometimes a person with two christened names dropped one and used the other. Example: Elizabeth M. (for Malane) Razor made a marriage bond in Owen County to marry Franz Hartman. Then she turned up on the Henry County census as Malane, wife of Frank Hartman. Possibly she dropped her first name of Elizabeth because she had a cousin also named Elizabeth.

Another problem was the reckless use of different names. For instance, the one who may be Mary on one record and Polly on the next were the same person. We pity not only the researcher but also the poor father who had four daughters-in-law named Catherine.

Was Your Kentucky Ancestor GTT?

In researching Kentucky ancestors between 1800 and 1860, sometimes a family (or more likely, a single man) moved to another state, like Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, Iowa, Tennessee, Alabama or Mississippi, and by all accounts just disappeared. For a while, the frequent answer to “What became of so and so?” was “Gone to Texas” or simply “GTT.” If a southern resident left their home, they might chalk “GTT” on the door.

Sometimes the going to Texas was to escape legal charges, bill collectors, a hostile neighbor, a family or a nagging spouse, and so the individual left without a trace for anyone to follow, then or now. In the beginning of the 1800s, Texas gained a reputation for harboring those who were “at outs with law” and GTT became common slang with a more ominous tone.

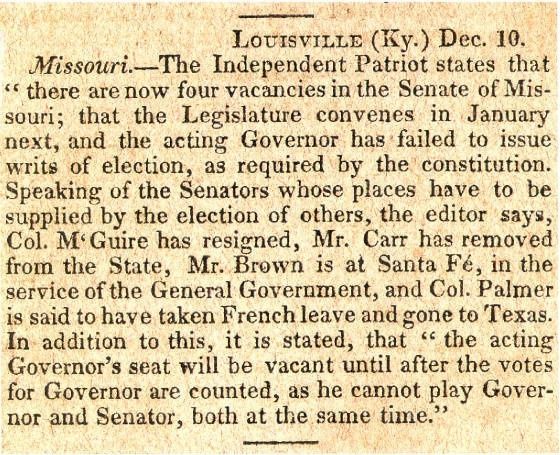

In a newspaper clipping from the December 29, 1825, edition of the National Gazette and Literary Register published in Philadelphia reporting that the Colonel Palmer was essentially GTT. [Public Domain, Wikimedia]

Was the Disappearance a Legal Reason?

Another possibility could be that of a name changed by legal process.

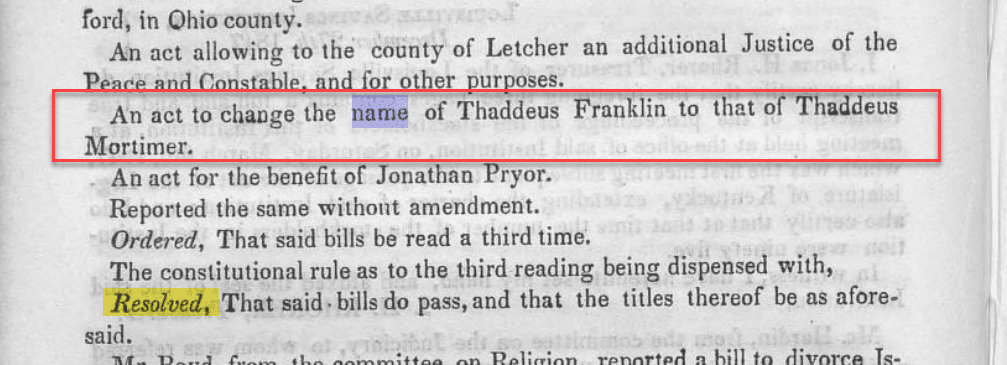

In the early years in Kentucky, a name change required an act of the legislature. Glenn Clift’s Divorce List of Kentucky divorces from 1792 to 1849 (published in 1980 Bluegrass Roots), contains many name changes. [Also, check out our Divorce: Kentucky Style post.]

Franklin is now a Mortimer. [Source: Journal of the Senate of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, December 31, 1847 – March 1, 1848, page 69]

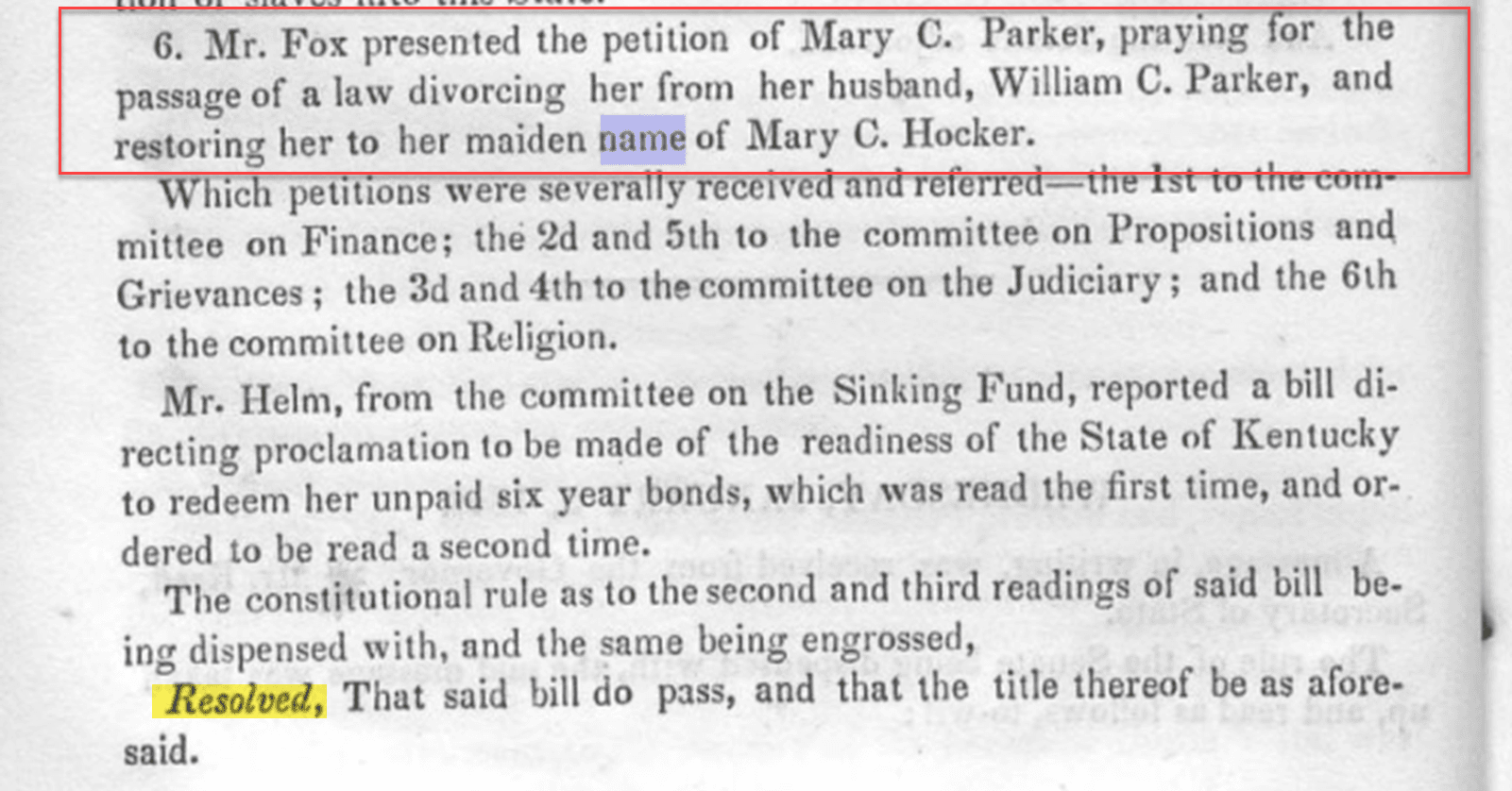

Most of these changes resulted from and followed divorces. And, several of these acts not only restored to a woman her maiden name but also gave her maiden name to her children. It might never occur to a researcher to look for children under their mother’s maiden name.

This shows how the divorce list can be useful in genealogy. So, if you have a lost person, you might try the name change possibility. If a name was changed in Kentucky between 1792 and 1849, it might be found on the divorce list.

Parker’s divorce granted and her maiden name restored. [Source: Journal of the Senate of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, December 31, 1847 – March 1, 1848, page 7]

The 1850 constitution outlawed special acts of the legislature, such as divorces and name changes. You can see how the legal name change could cause considerable trouble for future genealogists.

Story of a Hogg and a Hogue

One story illustrates the legislative name change. A man was named Hogg and thought it was beneath his dignity. He was such an overbearing, grasping character that those who knew him thought the name Hogg fit him right well.

Mr. Hogg applied to the legislature and got an act passed, changing his name to the more dignified Hogue. At the next lodge meeting, he pompously directed the lodge secretary to change his name on the lodge records to confirm.

Whereupon the secretary duly recorded:

Hogg by name,

Hog by nature;

Hogue by act

of the legislature.