Using Maps in Your Genealogical Research

No genealogist worth their salt does genealogy without the aid of maps. Maps are a tool used to understand our people and the land they walked on plus a means of cutting down research time. A county doesn’t appear large when you are comparing it to a state, but believe me, it suddenly takes on the proportions of a continent when you are there personally in the area, beating the bushes for your kin.

The first thing to do when starting research in a county is to review a map of the county. Specifically, you will want to review the back roads and find the locations of cemeteries. Why is it so important to use a map, especially when you are back in the area personally? How many times have you run the deeds and found that the name Fredrick Quackenberry is not so unusual at all, that in fact, the whole cotton-pickin’ county seems to be crawling with Quackenberrys!

Suddenly, you have that sneaking suspicion that some of these Fredrick Quackenberry may not be your Freddie. All of us have had this exasperating experience at least once. To help put the Quackenberrys in their place, you need a map. Most land descriptions in Kentucky relate to watercourses as do most of the other southern states.

By placing your Quackenberrys on the map through the use of the land descriptions in deeds and such, you will have a better idea of the area you will have to search thoroughly and interview people in. The problem of “which cemetery shall I search in?” is simplified — you will know the general area to search. Also, all the old churches in this general area should have their historic records checked. Your county has shrunk back down to a size you can work with more easily.

Maps come in all sizes, dates, and kinds. Let’s look at some and see what is available.

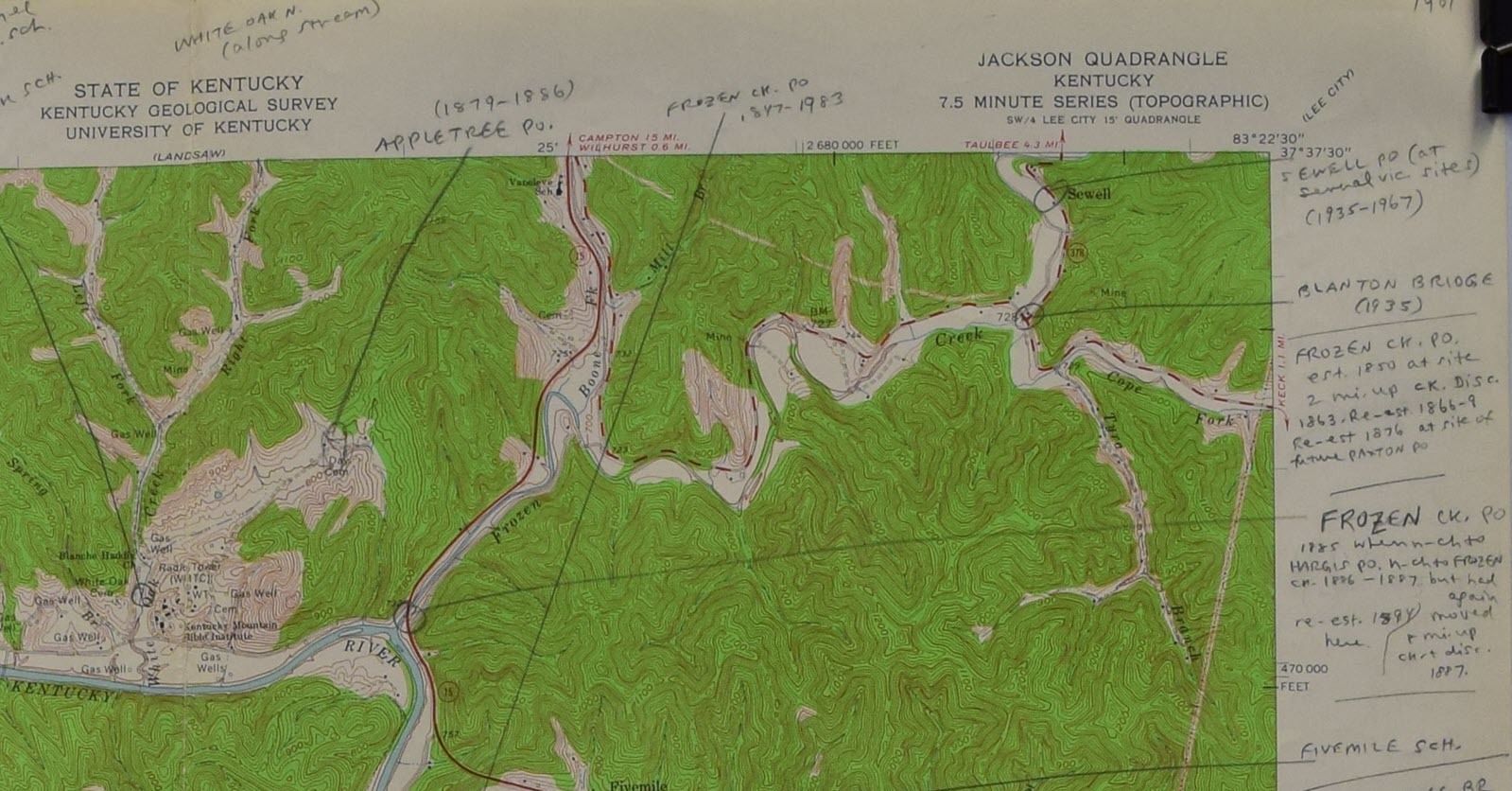

Use Topographic Maps to Understand Terrain

This type of map is valuable, as it shows the shape and position of landforms. It doesn’t take long to catch on to reading contours and within a short time you will be able to tell at a glance how low a valley is or how high a hill. Besides the height and depth appearance you will find streams, springs and lakes marked as well as roads, towns, and cities.

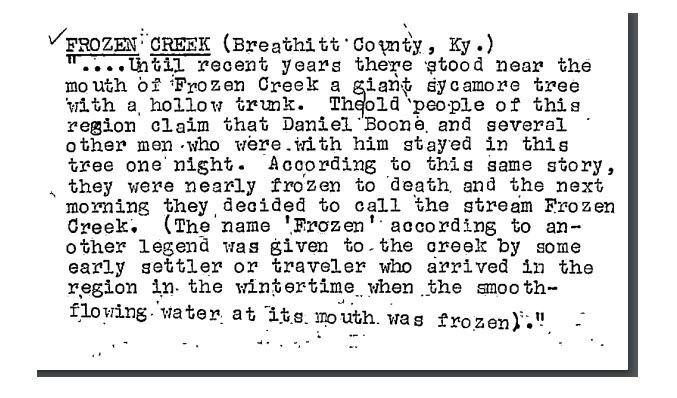

Breathitt County is mountainous, which may not be as clear on other maps. It is easier to understand where post offices and later towns arose. The maps in this collection contain Rennick’s notes. Source: Robert M. Rennick Topographical Maps Collection

Breathitt County Place Names from the Robert M. Rennick Manuscript Collection.

By studying these maps you can better understand why Uncle Freddie moved this way instead of that way. Freddie may have lived fairly close to the county seat as the crow flies but, being a mortal and not having wings, Freddie had to keep to the trails and roads that led around the mountains. it simply was easier to go to the neighboring county to get married, which didn’t have natural barriers that took a lot of time and effort to go around.

Another thing, more than likely those odd place names found in so many of the old records can be spotted on these maps.

An aid in helping spot those peculiar place names and one that should be used in conjunction with your topographical maps is A Guide to Kentucky Place Names by Thomas P. Field. This is a gazetteer or geographical dictionary that is indispensable when working with place names.

Tip: In the Morehead State University library digital archive, you can find the Robert M Rennick Manuscript Collection with Kentucky Place Names on cards.

Use Cadastral Maps to Understand Proximity and Ownership

The cadastral map is different from the topographical map in that it shows who owns property and the location of boundaries and sub-divisions instead of physical features. County atlases are properly called cadastral maps as they generally give names of landowners and the amounts of acreage.

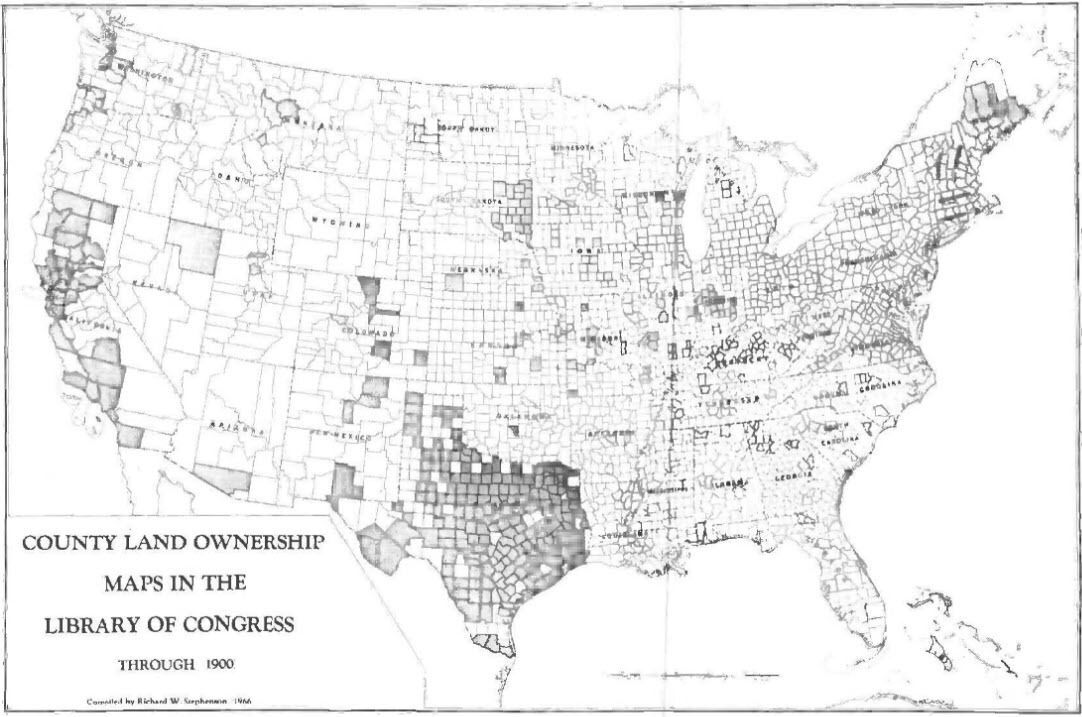

Two major collections of land ownership maps are housed at the New York City Public Library, Digital Collection, and the Library of Congress.

Tip: At either site, use the search term “maps Kentucky cadastral” to see the maps they have available.

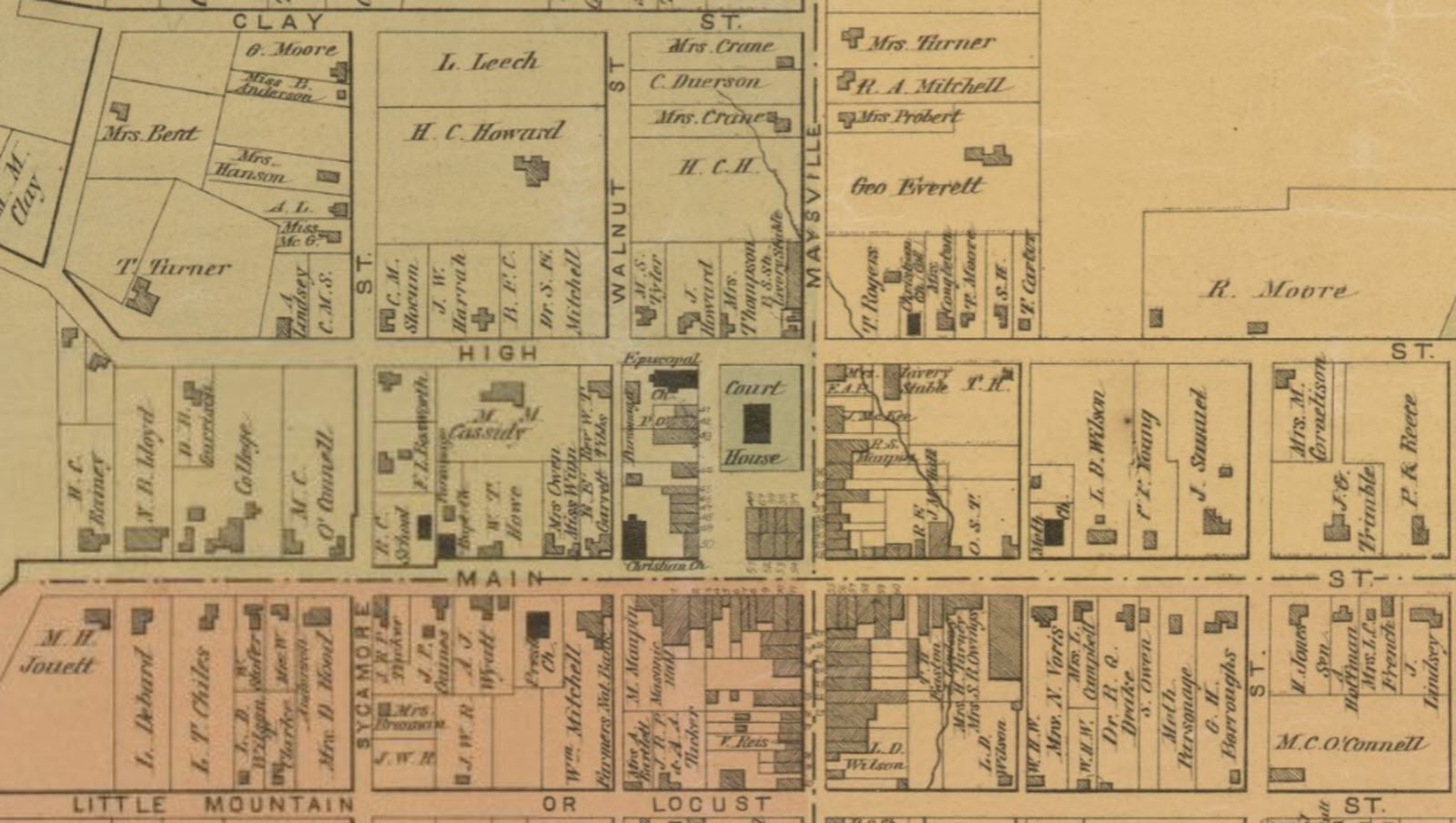

These nineteenth century land ownership (cadastral) maps found in the Library of Congress predate the more well-known county plat books and US topographical surveys. They are an indispensable tool to the genealogist for the giving of location of individual dwellings and names of occupants as well as churches, roads, villages, rivers, streams and schools.

The Library of Congress has eighteen maps in their digital archive including the following one from Montgomery County, KY. Their collection includes the following counties: Barren County, Boyle County, Christian County, Fayette County, Harrison County, Larue County, Madison County, Marion County, Mercer County, Scott County, Warren County, Washington County, and Woodford County. There are a few others that show specific areas or have limited names.

Cadastral map of downtown Mt. Sterling, Kentucky in Montgomery County from 1879. Source: Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.

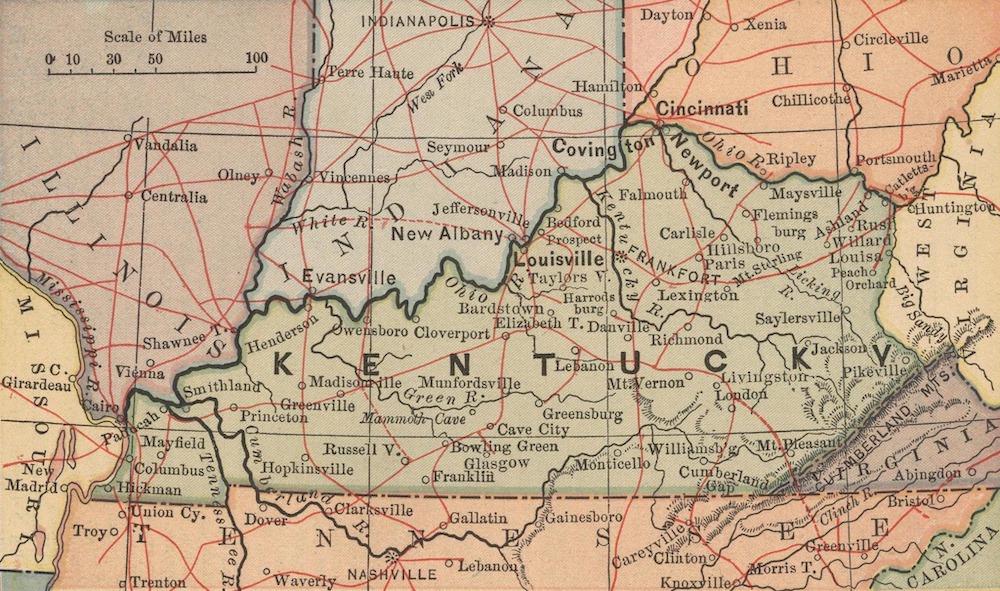

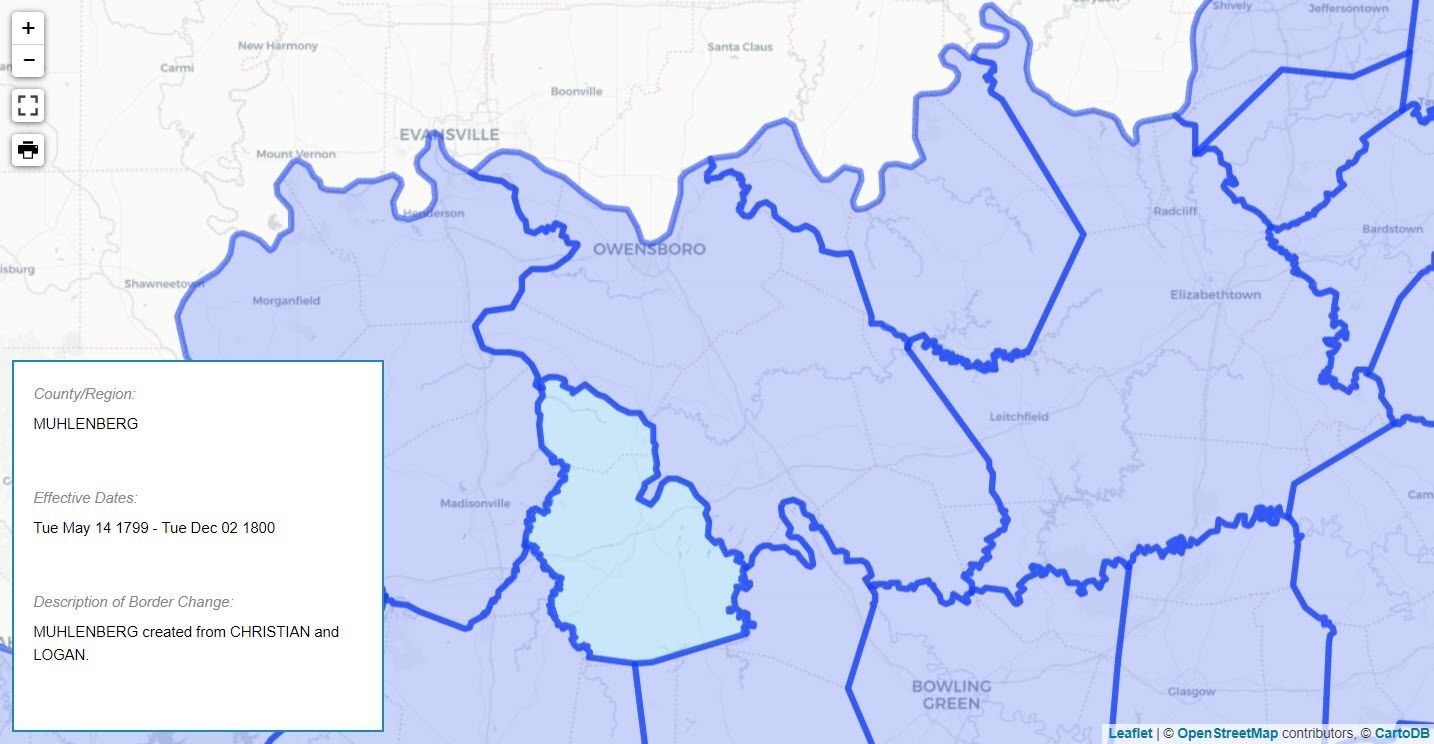

Use Historical Maps to Understand Boundary Changes

This category actually includes all maps that were printed showing a particular area or region at a particular period of time. The genealogist, if wise, will find a map that is near the time period that an ancestor lived in the area.

US Atlas site shows the historical maps overlaid on a current county map. This map shows the Muhlenberg County border changes in 1799. Source: The Newberry Library Digital Collection

Roads, county boundaries, and villages give clues as to routes traveled, new clues for searching in conjunction with boundary changes and long disappeared and forgotten villages and place names. With historical maps before you it is easier to step back into time.

Maps are Valuable to Family Research

A map is just a map when you first get it. It only becomes important to you when you use it — marking places where kin lived, locating their nearby neighbors (you later find them becoming relatives a good part of the time), spotting sites of old churches and cemeteries, ferries, fords, and so on.

References

Here are a few of our favorite sites for Kentucky maps:

- David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

- Randy Majors Research Hub

- Newberry Library: Index of Kentucky County Maps Overtime

- Kentucky Department of Transportation Maps (Order a free Kentucky Highway map!)

- Kentucky Atlas and Gazetteer

Editor’s Note

This post was excerpted from the author’s Kentucky Genealogical Research Sources manuscript, which is available from the Family History Library. We updated the 1974 text with the more recent references and added artwork for clarification.