Was He a Coal Miner?

Along with tobacco, racehorses, and bourbon, coal has long been part of the defining narrative of Kentucky’s history. Serious coal mining in Kentucky had its modest beginning in 1820 with the opening of a commercial mine in Muhlenberg County, but it wasn’t until the late nineteenth century that coal became a significant factor in the economy of the commonwealth. By the time of the first world war, railroads had connected mountain coal and timber operations with urban industrial centers, and the die was cast.

Celebrating the Coal Mining Empires

Coal camps sprang up like mushrooms across eastern Kentucky, as well as Kentucky’s western coal field. The labor demands of the coal industry were substantial, and commercial coal mines, both in the western area of the state and throughout the larger eastern coalfields of Appalachia, have employed hundreds of thousands of workers over the last century and a half.

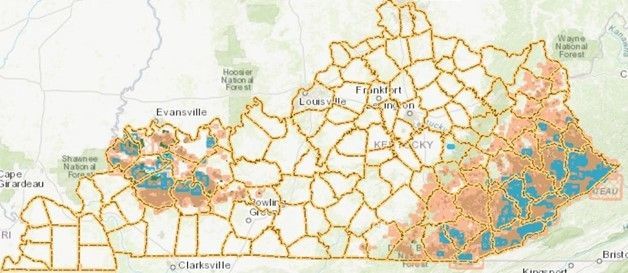

The Kentucky Coal Fields, east and west. Source Kentucky Coal Mine Maps

Although by the beginning of the twentieth century, politicians and industrialists were celebrating the establishment of substantial coal mining enterprises in coal-rich areas of the state, the coal industry in Kentucky has been steeped in controversy for well over a century.

Nearly sixty years ago, Harry M. Caudill identified the coal industry as being almost entirely responsible for the dire poverty of southern Appalachia, as well as serious and perhaps irreparable damage to mountain ecosystems. He described at length the ruthless exploitation of naïve Appalachian mountaineers, who surrendered their timber and mineral rights for a pittance and then found themselves without the wherewithal to make a living.[1]

They ended up working in the coal mines to survive, giving up their lands, their homes, and much of their fierce independence. This set of circumstances solved the immediate crisis – looming starvation – but left the miners with an assortment of fresh problems, many of which have not been satisfactorily resolved to this day.

Working in the Coal Mines was Dangerous

Mine safety was and continues to be, a serious concern. Coal mining has historically been a highly dangerous activity, with enormous potential for catastrophic accidents resulting in multiple injuries and deaths among workers. As Jacqueline Karnell Corn observed in a 1983 article

The major hazards of coal mining – inadequate or improper ventilation, poor illumination, accumulation of dust, dangerous gasses, use of explosives, poorly supported roofs and unsafe haulage ways –– all conspired to make coal mining an extraordinarily perilous occupation. Explosions of gas or dust, fires, haulage accidents, roof falls, and inundations grew more deadly and affected more men with the deepening, extending and mechanization of the mines.[2]

Corn also addressed the chronic respiratory diseases that plagued miners because of the unhealthy environments in which they labored, and she noted, “Respiratory disease caused by dust – miner’s asthma, silicosis, and pneumoconiosis – killed men as surely as mine accidents.”[3]

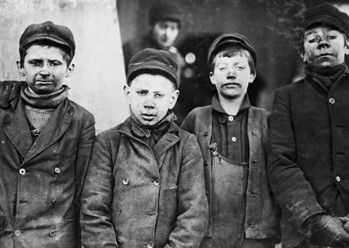

West Virginia boys stand near the coal mine in which they work. Date unspecified. Lewis Hines, National Child Labor Committee, Collection of the Library of Congress.

To compound the problem of mine safety and the lack thereof, Kentucky coal mines, along with mines in Alabama, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania, drew considerable attention from the National Child Labor Committee in the early 20th century. Mines routinely employed children as young as nine years old, as breaker boys, tipple boys, trapper boys, and drivers, not only depriving them of the opportunity to go to school but also subjecting them to many of the same dangers as adult miners, and other hazards related to their youth, immaturity, inexperience, and small stature.

Many of these youngsters worked ten to twelve hours a day inside the mines. As these conditions became more widely known, child welfare advocates demanded reform, and partly because of the efforts of photographers like Lewis Hines and activists like Mary Harris Jones (Mother Jones), the Keating-Owens Child Labor Act was passed by Congress in 1916, specifying 16 years as the minimum age for mining work.

Several powerful industries that routinely employed child workers vociferously protested that act, and the Keating-Owens Act was later ruled unconstitutional. Real reform in this area was appallingly slow in coming.[4]

Additional labor issues developed or intensified, as concerns about long hours, low wages and pay cuts, inconsistent and/or seasonal work availability, hazardous working conditions, and various other problems led to heated and often violent conflicts between miners attempting to unionize and the mining companies that employed them. They often described Union representatives as dangerous Communist radicals, as the coal companies attempted to dissuade their workers from joining, first with anti-socialist rhetoric and name-calling, then with threats and physical violence. Nevertheless, the United Mine Workers of America made substantial inroads into the region, and they unionized many mines by the mid-twentieth century.

Finding Ancestors in Periodicals and Mining Records

As a result of the conditions and long-time controversy surrounding coal mining in Kentucky, including several violent confrontations between miners and coal operators that made national news, you may find mention of your mining ancestors in several places. There are many resources available to discover more information about Kentucky coal mines, but it’s challenging to find information about a specific individual.

Lists of mining accidents, including injuries and fatalities, can usually serve only to support information you already have, as they rarely list casualties by name. Start with stories and recollections from your own family members and work out from there. If you have a name, date range, and approximate location for your miner, checking with the county historical society can often give you a running start. The Knox County Historical Society, for example, offers a downloadable chart with employment records, including names, places, and nearest relatives, for the Jellico Mining Company.[5]

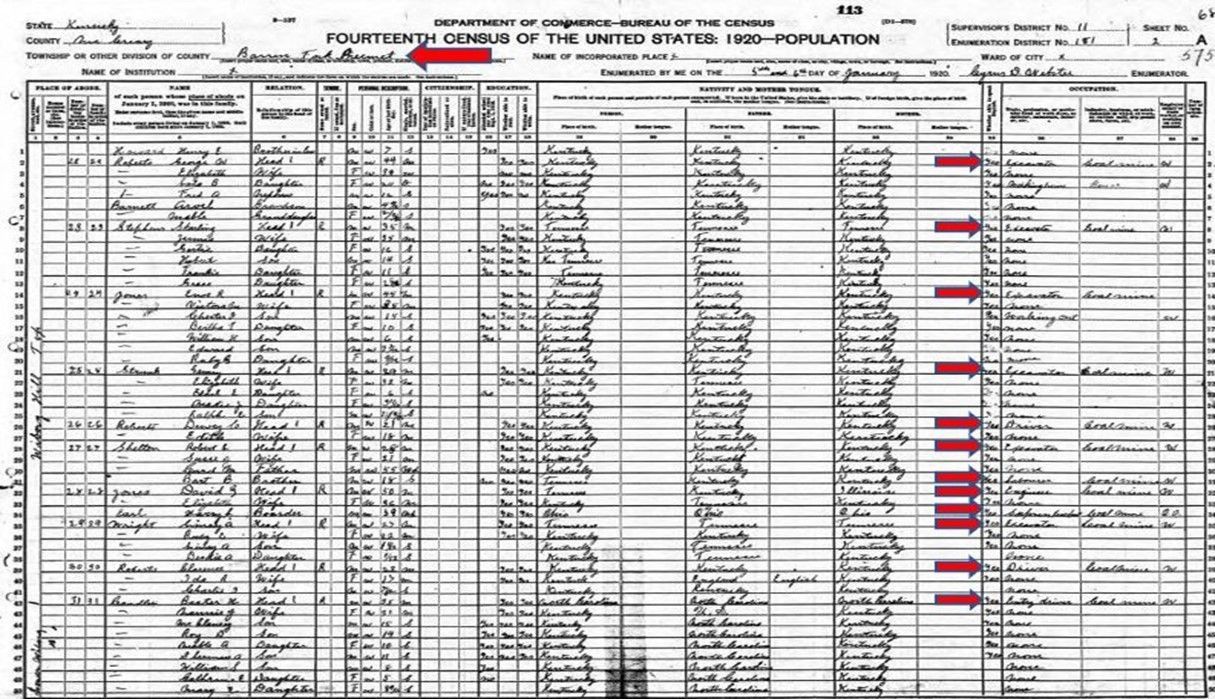

Census data can be very helpful in finding your coal mining ancestor; he may be identified as a coal miner in one or more census reports. Note that if you encounter a census page in which every single head of household on the page is a miner, you can usually assume that he and his family and neighbors lived in a coal camp, as stated in the example below.

Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920: McCreary County, KY. Barren Fork Precinct. Barren Fork was indeed a coal camp. One of my ancestors died there in a mining accident.

The Mine Data Retrieval System maintained by The Department of Labor is an excellent resource if you know exactly what you’re looking for. You can search for specific mines by name and/or location.[6] Another invaluable resource is the Kentucky Mine Accident Index, [7] which can be downloaded as a PDF file in its entirety. It lists individuals by name, date, county, and mining company, and shows whether the injury sustained was fatal.

Other Mining Resources

Historical documents and photographs maintained and archived by the US government are accessible to researchers, and some resources are available online. These include (but are not limited to) collections of the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and the aforementioned Department of Labor. Internet Archive has many issues of old coal mining trade journals, such as Saward’s Journal, Coal Age, and Coal Mining. These publications include little data specific to individuals, but they provide some fascinating information about coal mining technologies, tools and equipment, health and safety issues, and other aspects of the industry, which can be very useful for historical context.

Newspapers often carried news of coal mines, including companies looking to hire workers, reports of accidents and fatalities, political analyses (especially during election years), various lawsuits, union activities, and other newsworthy information. Again, the information contained can be very helpful in providing historical context, as well as in highlighting the controversial aspects of the industry, and in describing the many conflicts between miners and coal operators.

The highly politicized nature of the coal mining industry in Kentucky in general and in Appalachia in particular is laid bare in many of these old newspaper accounts, and they can provide fascinating and occasionally disturbing reading. There are many vintage newspapers available for Kentucky coal counties, thanks to the Kentucky Digital Newspaper Program, made available at Internet Archive through the University of Kentucky Libraries.[8] These issues can be downloaded for examination at your convenience.

Researching My Coal Mining Roots

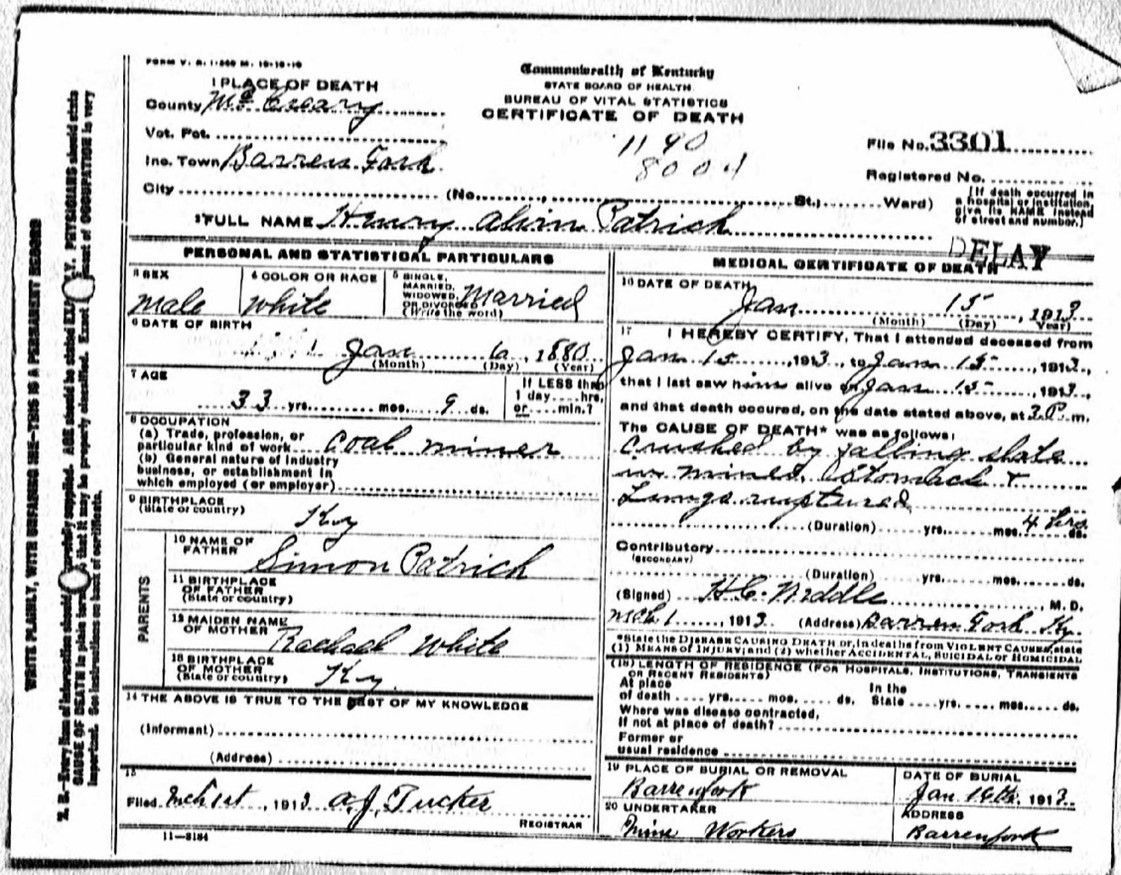

I discovered my own Kentucky coal mining ancestor entirely by accident. While investigating my great-grandmother’s various marriages in the early twentieth century (she was widowed three times in less than 15 years), I started looking more closely at her siblings. I discovered a death certificate for one of her brothers, Henry Alvin Patrick. I was familiar with his name, as he had been present at her marriage to my great-grandfather in 1900, and he was named on her marriage record as a witness. His death certificate revealed Henry had worked as a coal miner and was killed in a dreadful mining accident at Barren Fork in 1913. A young man at the time of his death, Henry left behind a wife and six children. In the 1910 census, Henry was listed as a farmer, and by 1920, he was deceased, so his brief tenure as a miner was news to me.

Death certificate for Henry Alvin Patrick, Barren Fork, McCreary County, KY January 15, 1913. Cause of death states, “Crushed by falling slate in mine. Stomach and lungs ruptured.”

Although I currently live within 30 miles of the site of the old Barren Fork mine in McCreary County, I had never heard of either the mine or the town, so I did a quick Google search and discovered quite a lot of information. As was often the case, the mine was the town. Henry appears as H. A. Patrick, listed as a fatality in the Kentucky Mine Accident Index. The name of the coal company was given as Eagle Coal (misspelled, as you see), which owned the Barren Fork mine along with several others in the area.

I contacted the public library in McCreary County, which is also the home of their county historical society, and I was informed that the site of the old Barren Fork mine can be toured by visitors, that the original building that housed the general store that served the coal camp is still standing, and that the cemetery where Henry is buried is also there on the Barren Fork property.

Interestingly, my Google search also uncovered a transcribed legal document that mentioned Henry Patrick. Henry’s widow, or someone acting on her behalf, sued the Eagle Coal Company in 1913 in a wrongful death action, alleging that the company had failed in its responsibility to provide a safe work environment. The court agreed, and Henry’s heirs were awarded $2,750 by the court.

However, it appears that coal companies had no such responsibility, or at least none that was enforceable by law or that rendered the company liable. The coal company successfully appealed the award the following year, and the family received nothing.

This was not at all uncommon, as the law, the courts, and the local politicians in coal country were often under the sway of and/or being paid by influential and unscrupulous coal operators, but it must have been heartbreaking for the grieving family. I have yet to determine where Henry’s family resettled, since they would not have been able to remain at the coal camp after his death. I’m hoping to uncover more information about the original lawsuit and the family’s later location when I visit the McCreary County Public Library and investigate the site of the old Barren Fork mine.

These discoveries reinforced my interest in Kentucky coal mining, and I’m still engrossed by its fascinating and often tragic history, and my family’s small part in it. I hope this information will be helpful to you as you research your own coal mining ancestors.

Editor’s Notes

The post title refers to a popular 1950s song. The author added this note about it.

“Sixteen Tons” is a reference to an old coal mining song, performed and recorded by Tennessee Ernie Ford in 1955. I remember hearing it on the radio when I was a young girl. The song was so popular it was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1998, and in 2015 it was declared to be among the top ten Labor Day songs by The Nation. Ted Olsen, “16 Tons,” Tennessee Ernie Ford, (Library of Congress, 2014), https://www.loc.gov/static/programs/national-recording-preservation-board/documents/16Tons.pdf, accessed Nov. 22, 2021.

References

[1] Harry M. Caudill, Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Area. (New York: Little, Brown Co., 1964), 77-79.

[2] Jacqueline Karnell Corn, “’Dark as a Dungeon:’ Environment and Coal Miners’ Health and Safety in Nineteenth Century America,” Environmental Review: ER 7, no. 3 (1983): 258. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3984483, accessed Nov. 10, 2021.

[3] Corn, 265.

[4] Owen R. Lovejoy, “Child Labor in the Coal Mines,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 27, Child Labor (Mar. 1906), pp. 35-41. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1010788. See also “Children of the Kentucky Coal Fields,” in The American Child (New York: The National Child Labor Committee, Feb. 1920). The entire issue is devoted to an analysis of children working in, or otherwise associated with, Kentucky coal mines.

[5] Employment Records From the Old Kentucky-Jellico Mining Company, Knox Historical Museum, History, and Genealogy Center, Barbourville, KY, https://www.knoxhistoricalmuseum.org/history/of-knox-county-kentucky/coal-mining-history/652-employment-records-from-the-old-kentucky-jellico-mining-company.html, accessed November 3, 2021.

[6] Mine Data Retrieval System, United States Dept. of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Division. https://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/070.html, accessed Nov. 3, 2021.

[7] Kentucky Mine Accident Index, US-KY-Index-Mine, https://miningquiz.com/pdf/Accidents/US-KY-IndexMine.pdf, accessed Nov. 21, 2021.

[8] Kentucky Digital Newspaper Program, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/kentuckynewspapers, accessed Nov. 6, 2021.