After the Civil War, some formerly enslaved people sought reparations in courts of law. The most successful among them was Henrietta Wood from Kentucky. She won compensation for some of her unpaid labor and became one of the few who got reparations for years of slavery in America. And yet, after only a couple generations, her ancestors had no knowledge of her strength and determination.

In 1876, Wood told her story to Lafcadio Hearn, a reporter for the Cincinnati Commercial newspaper.

Wood reported that she’d been born into slavery, on the farm of Moses Tousey, along the Ohio River, in Boone County, Kentucky. She was a young teenager when her owner died, and all the slaves were sold. She told the journalist, “I was taken together with my brothers and one sister to Louisville and sold there to Mr. Henry Forsythe for $700. He did not buy my brothers and sisters, and I never saw them since.”

According to Dan Gediman, who told Henrietta’s story in the podcast The Reckoning,Wood’s story was a typical one for the time. She worked in Forsythe’s home in Louisville until he sold her to a French immigrant, William Cirode, who took her to New Orleans. When Cirode abandoned his family and went back to France, his wife, Jane Cirode, moved the family to Cincinnati, Ohio, and opened a boarding house, eventually bringing Henrietta with her. The move to Cincinnati was pivotal for Wood.

Her Sweet Taste of Liberty

W. Caleb McDaniel is a professor of history at Rice University and author of a book about Henrietta Wood, which won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for History. McDaniel says Jane Cirode did just as she was required by Ohio law. In 1848, she went to the county courthouse in Cincinnati and recorded Henrietta as a free person, so she could legally work in Cirode’s and other boarding house. The next few years were what Wood referred to as her sweet taste of liberty.

Cirode rarely paid Henrietta, so she sought work from others in Cincinnati, including Mrs. Boyd, the wife of a dentist and a boarding house owner.

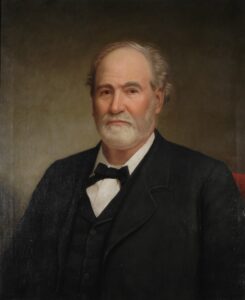

Zebulon Ward, kidnapper and enslaver of Henrietta

In her interview, Wood recalled one Sunday in 1853, Mrs. Boyd asked her to go on a carriage ride over the Ohio River to Kentucky. She had no idea she was about to be kidnapped and sold back into slavery. In Covington, the carriage was stopped by several men, including Zebulon Ward, a deputy sheriff. Henrietta saw him give Mrs. Boyd a roll of money. Then she was transferred to another wagon. They didn’t stop until they reached the small town of Florence, Kentucky, far enough away from Covington and the Ohio River to impede any attempt to flee back to Ohio.

Kidnapped in Kentucky

From the beginning, Wood declared that she was free and it wasn’t right to sell her back into slavery, Dr. McDaniel relates what happened next.

“Wood began telling her story, almost from the earliest hours of her abduction,” he said. “She was taken to a roadside inn in Florence, where many travelers would stop after making the long climb from the Ohio River. While she was confined by her abductors, she told what had happened to a sympathetic innkeeper, a man she remembered as Mr. Williams. He followed her to Lexington where the kidnappers intended to sell her to slave traders. Mr. Williams helped her file a lawsuit in the Fayette County court that argued Henrietta Wood was rightfully a free woman.”

Williams helped Wood get an attorney to take advantage of a legal process that most southern states had at the time, referred to as a “freedom suit,” where people could sue to show that they were wrongfully enslaved. It required the assistance of someone who was free to appear on their behalf before the court. But it did allow some people to tell their story if they had been kidnapped. And that’s what Wood did. A suit was filed in 1853. It dragged on for another year before the court ruled against her and dismissed her petition for freedom. After that, her lawyers appealed the case, but the lower court’s decision was upheld. The paper that declared Wood to be legally free was not in her possession, and the record filed in the courthouse was gone due to a fire. So, two years after her freedom suit began, she was ruled to be the slave of Zebulon Ward.

During that time, Zebulon Ward had become the keeper of the Kentucky state penitentiary, so he took Henrietta to Frankfort, Kentucky’s capital, where she worked as a slave in his home. Eventually, he sold her to slave traders who took her to Natchez, Mississippi.

Illustration depicting Henrietta Arthur. No photo of her known to exist.

She was purchased for $1,000, to work on a cotton plantation owned by Gerard Brandon.

According to Dan Gediman, Brandon was one of the largest slave owners in the country. While in Mississippi, Wood gave birth to a son, Arthur. When Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Brandon marched all his slaves from Mississippi to Texas to keep them away from Federal troops. The 13th Amendment in December 1865 ended slavery, but it would take Wood another three years to be completely free of Brandon. When she was finally able to scrape together enough money, she took her son and headed north.

Wood returned to the Cincinnati area. In 1870, she engaged a lawyer, Harvey Myers, in Covington, Kentucky, to file a suit for restitution. She was suing for the damages caused by her abduction in 1853, but also for the wages she lost while enslaved by Zebulon Ward and Gerard Brandon. She sued for $20,000, based on an estimate that she could have made $500 per year as a free woman plus damages. In the end, she received only a fraction of that amount.

The petition made clear that this was not just a suit about her kidnapping, but it was really about slavery itself and about the unrequited toil that she had endured for so many years, said the author McDaniel. However, based on the judge’s instructions to the jury, he added, it appears the jury viewed the case in a much more restricted way and based the award strictly on her kidnapping.

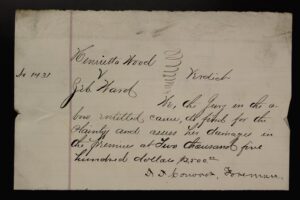

The Verdict

This is the jury’s decision in favor of Henrietta and grant her $2,500.

Her trial suffered a setback in 1874, when her attorney was killed. In 1878, a jury decreed that Wood was owed $2,500 (about $68,000 today).

Wood put that money to good use. She and her son, Arthur Sims, moved to Chicago, where she paid cash for a house. Arthur was then able to borrow money based on the home’s equity to buy two more houses and pay for his education. He became one of the first African American graduates of the Union College of Law, which later became the Northwestern University School of Law. Arthur practiced law in Chicago until his death at age 95 in 1951.

Henrietta Wood’s son, Arthur Sims, was a lawyer in Chicago.

After the case closed in 1878, it received ample publicity. By the time Henrietta died in 1912, her story was long forgotten until McDaniels began research for his book. He found Winona Atkins, a great-granddaughter of Arthur Simms. Winona remembered her great-grandfather and even lived with him in his Chicago home as a young child. She told McDaniels that she had no idea that Arthur had been a slave, and she did not know her great-great-grandmother’s story.

Separately, David Blackman, another great-grandchild of Arthur, found some copies of papers about Henrietta when he was cleaning out his mother’s house after her death. He was intrigued by the age of the documents and wondered why his mother had saved them. She had never told him about Henrietta and Arthur’s history.

Woods’ victory was extraordinary and, in some ways, exceptional. But her predicament was not uncommon at all,. Free people of color living along the Ohio River Valley, were at constant risk of being kidnapped and sold into slavery, especially after the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. That law made it much easier for would-be enslavers to enter free states, claim that a free person of color was actually a fugitive slave, and without providing much evidence to demonstrate their case, they could take a person back into Kentucky, and sell them far down the river before a hue and cry could be raised. Many abolitionists at the time raised awareness of this problem. The newspapers contained many stories of kidnappings from the streets of cities like Cincinnati.

During the antebellum period, many southern states made it much more difficult for plaintiffs to sue for freedom in state courts, and even more difficult to recover restitution for what had happened to them. In fact, many states, including the Commonwealth of Kentucky, passed laws that said restitution in a freedom suit could only be awarded in cases where the defendant had knowingly enslaved a free person. But if the defendant could demonstrate that they had enslaved the person, “in good faith,” then no restitution claim could be made against them. And, not surprisingly, most of the defendants, who were like Zebulon Ward, claimed that they had no idea this person was free. And so, restitution was seldom paid.

Henrietta’s Legacy

According to a story in the Borderlands Archives and History Center at the Boone County, Kentucky, library, Henrietta left more to her descendants than the financial boost from the lawsuit. A more precious gift was the example of her unrelenting fight for justice; a show of strength and confidence for the generations who followed her. Among her descendants are musicians, professionals, academics and even a Tuskegee Airman. Her legacy is one of resilience.

A 2021 article in The Washington Post wondered if Henrietta’s descendants have inherited any traits from her and Arthur, even though they never talked about their history. Sydney Trent, who wrote The Washington Post article, interviewed Nick Sheedy, lead genealogist on the PBS series “Finding Your Roots.” Sheedy said, “Whether we realize it or not, every little decision our ancestors made charted a path for us as their descendants. And the decisions we make today affect the people who come after us. History isn’t some static set of facts. … We are connected to history today.”

Note: a major source for this story is The Reckoning: Facing the Legacy of Slavery in America (https://reckoningradio.org/podcast/the-reckoning/.) Reckoning, Inc. is a non-profit organization whose mission is to examine the legacy of slavery in America, especially in Kentucky, and to create ways for communities to engage with this information through research projects, media productions, educational curricula, online content, and other means. In addition to The Reckoning podcast, which includes more stories about Kentucky during the Civil War, Reckoning,Inc., also features on its website the Kentucky Black Ancestors Database, which contains records of over 100,000 Black people who were living in Kentucky before 1865, whether enslaved or free. The website also has the Kentucky Enslaved Catholic Church Records Database, which contains over 5,000 baptismal, marriage, and burial records for people who were enslaved by Catholics in Kentucky, and the Kentucky African American Civil War Soldiers Project, which has resulted in the creation of family trees for over 750 of Kentucky’s Black Civil War soldiers.

For more a more detailed story of Henrietta Wood’s life, read W. Caleb McDaniel’s book, Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America. It is extremely well documented and reads like a novel.

Bibliography

“Henrietta Wood,” Cincinnati Sites and Stories, Borderlands Archive & History Center at the Boone County Public Library, accessed July 17, 2025, https://stories.cincinnatipreservation.org/items/show/178.

Caleb McDaniel. “In 1970, Henrietta Wood sued for Reparations—And Won,” Smithsonian Magazine, (September 2017); https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/henrietta-wood-sued-reparations-won-180972845/

McDaniel, Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019)

“She sued her enslaver for reparations and won. Her descendants never knew,” Sydney Trent, The Washington Post, February 24, 2021, accessed at https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/02/24/henrietta-wood-reparations-slavery/ July 21, 2025

“Story of a Slave,” Cincinnati Commercial, (April 2, 1876): p.2

The Reckoning: Facing the Legacy of Slavery in America, Reckoning, Inc.(https://reckoningradio.org.) Dan Gediman, Executive Director